Scientists Discover A Girl With DNA From Two Different Species

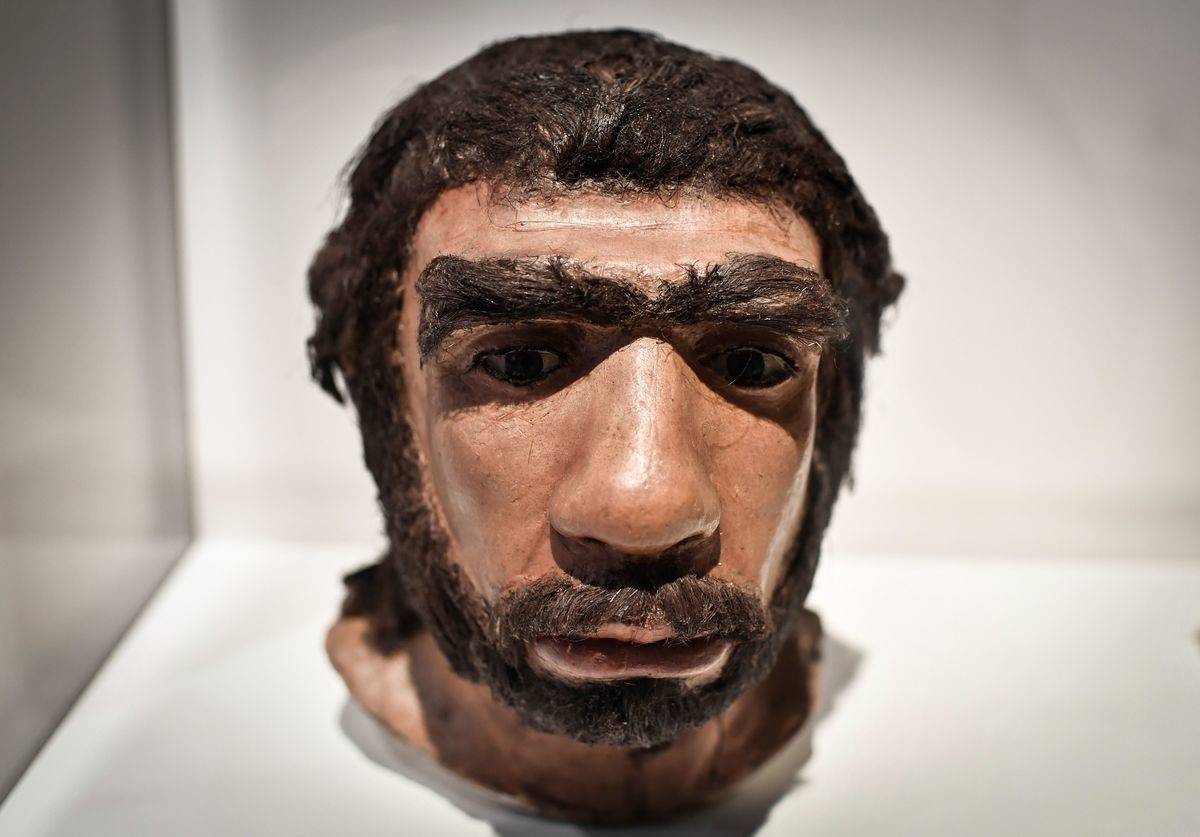

Modern humans evolved from Homo sapiens, and a small percentage of us have Neanderthal DNA. But did you know that there were more species of ancient humans? A newly-discovered girl had parents from two different species-- one Neanderthal, and another one that was recently discovered. This discovery will change our perception of human evolution.

Thanks to modern DNA tests, people can see whether they are part Neanderthal. Neanderthals are an extinct subspecies of humans that went extinct 40,000 years ago. Today, only 2% of Eurasians have Neanderthal DNA.

But there are more species of humans that existed thousands of years ago. A few recent discoveries have found a third species of ancient human that might have contributed to our ancestry. But how is that possible, and what happened to them?

The Third Species Of Human, Denisovans

In southern Siberia, Russia, there is a cave near the Altai Mountains called the Denisova Cave. It was named after an 18th-century hermit who lived there. In 2008, archaeologists from the Russian Academy of Sciences unearthed several bone fragments there.

Scientists dated the oldest bones to at least 51,000 years ago. But it was not a Neanderthal or Homo sapien; researchers from the Max Planck Institute announced that it was a new species of human, the Denisovan.

Who Were The Denisovans?

Beyond their DNA sequencing, little is known about the Denisovans. We know that they lived as far back as 217,000 years ago, but few Denisovan bone fragments have been found. Only five viable specimens have been analyzed to date.

But scientists had no idea that a new discovery would come out only a few years later. This ancient human was not just Denisovan; she was an interbred between two different human species, which challenges what we previously knew about human evolution.

Can Human Species Interbreed?

Interbreeding can be confusing. For instance, why do Neanderthals and Homo sapiens successfully interbreed, but mules (a cross between a horse and a donkey) become infertile? The answer lies in DNA.

A horse has 64 chromosomes, and a donkey has 62. When a mule is born, it gets 63 chromosomes-- an odd number, which is a "defective" genetic code. DNA needs to latch onto an even amount of chromosomes, 50% of the father's and 50% of the mother's.

The Key To Successful Interbreeding: Fertility

Although mules are infertile, plenty of other species can create fertile offspring. For instance, a liger (mix between a tiger and a lion) is fertile. These species are genetically compatible, just as many primates are also compatible.

Knowing this, it makes sense why Neanderthals and Homo sapiens could successfully interbreed. Researchers predicted that Denisovans also interbred with other human species, whether their offspring became fertile or not. However, they never found proof of this hypothesis until 2018.

In 2012, Archaeologists Had No Idea What They Would Find

In 2012, Russian archaeologists were once again examining the Denisova Cave. They uncovered multiple bone fragments, but they could not identify most of them. The archaeologists gathered a collection of 2,000 bone fragments and sent them to a lab.

These bone fragments sat untouched and unresearched for several years. Then, in 2016, a student at the University of Oxford discovered that one of these bone fragments was not like anything scientists had ever seen before.

Not Your Average Two-Centimeter Bone

Samantha Brown, an MSc student at the University of Oxford, was analyzing the 2,000 bone fragments in 2016. She was testing the DNA to determine what type of animal each bone belonged to. But to her surprise, at least one bone, only two centimeters long, ended up being human.

Knowing that Denisova Cave has a history of housing human remains, Brown looked closer. What she found was so shocking that she initially believed she had made a mistake.

What Did This College Student Discover?

Brown discovered that this human fragment was a unique result of interbreeding. The person was part Neanderthal and part Denisovan. If her results were accurate, then this would be the first evidence of first-generation breeding between two human species.

Brown contacted the head of the department, and then the bone fragments were sent to the the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. This Institute had the technology to closely examine the bone fragment and confirm Brown's results.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!