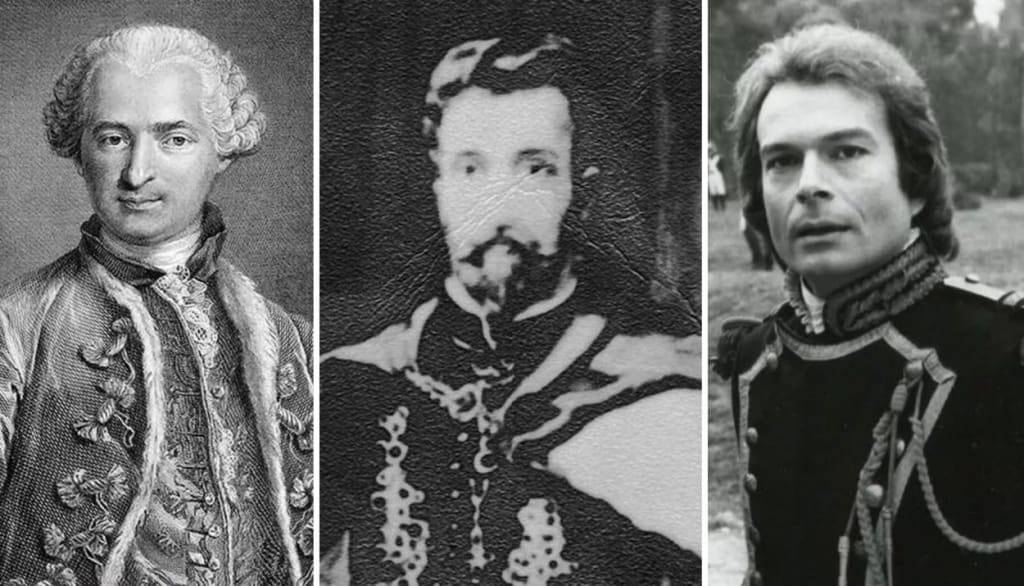

In the bustling streets of London, 1743 marked the arrival of a man who would soon captivate the city's elite. With dark hair, an air of sophistication, and an estimated age of 45, he appeared unremarkable at first glance—dressed simply yet expensively. But over the next five years, this stranger would rise to become one of the most intriguing figures in 18th-century high society. His name, or at least the one he gave, was the Count of Saint-Germain. Who was he? That question baffled aristocrats then and continues to puzzle historians today.

What set this man apart wasn’t just his polished appearance. He was a virtuoso violinist whose haunting melodies could reduce audiences to tears, a composer who penned works for London’s thriving opera scene, and a conversationalist with a mind like a steel trap. Whispers swirled that he spoke every European language as fluently as a native—French, Italian, Spanish, even Polish—and possessed a knowledge of history so vast it seemed he’d lived through it all. Then there were the wilder tales: that he could erase flaws from diamonds, transmute base metals into gold, and perhaps most tantalizingly, that he’d unlocked the secret to eternal life. But beneath the dazzle lay an enigma—no one knew where he’d come from or who he truly was.

In a world where lineage was everything, the Count’s lack of a past was astonishing. Aristocrats proudly traced their families back centuries, yet this man seemed to materialize out of thin air. He was undeniably educated, his violin skills rivaled the masters, and his wealth was evident, but no one could pinpoint his origins. No school claimed him, no mentor explained his talents, and no paper trail hinted at his fortune’s source. To London’s upper crust, he was a walking contradiction—a nobleman without a history.

A Star Rises—and Falls—in London's Spotlight

The Count’s arrival coincided with a golden age of curiosity, and he wasted no time making his mark. His musical talent earned him early fame; contemporaries ranked him among Europe’s finest violinists. But his charm and intellect soon propelled him beyond the concert hall into the drawing rooms of the elite. Horace Walpole, the sharp-tongued writer and son of a former prime minister, captured the confusion in a 1745 letter: “He sings, plays on the violin wonderfully, composes, is mad, and not very sensible… He is called an Italian, a Spaniard, a Pole; a somebody that married a great fortune in Mexico and ran away with her jewels to Constantinople.” Even the Prince of Wales was intrigued, though his fascination yielded no answers.

Yet in 1745, the Count’s mystique took a darker turn. Amid the Jacobite Rebellion—a bid by Bonnie Prince Charlie to claim the British throne with French backing—his flawless French and shadowy origins raised suspicions. Was he a spy? Authorities arrested him, demanding explanations. He offered none. The title “Count of Saint-Germain,” he admitted, was neither real nor his birth name. Facing a flimsy cover story, one might expect harsh consequences, but the Count’s charisma and high-placed friends worked their magic. He walked free, resuming his glittering social climb as if nothing had happened.

A French Adventure and a Bold Claim

By 1748, the Count bid farewell to England, resurfacing in Paris where the French aristocracy embraced him with even greater fervor. Here, he mingled with luminaries like Giacomo Casanova, the infamous adventurer who dubbed him a “perfect ladies’ man,” and Voltaire, the philosopher who wryly called him “a man who does not die and knows everything.” His reputation soared, fueled by a claim that turned heads: he was over 300 years old. Far from hiding it, he shared this audacious assertion freely, hinting at an alchemical breakthrough—the elixir of immortality.

Could it be true? His talents lent the idea some credence. Fluency in a dozen languages, mastery of the violin, and a knack for recounting historical events with eerie detail suggested a life far longer than most. In Paris, he charmed Louis XV and his mistress, Madame de Pompadour, convincing the king he held a secret dyeing technique to transform French textiles. The monarch granted him a factory, though the promised revolution never materialized. Later, in 1760, Louis dispatched him to Amsterdam to broker peace in the Seven Years’ War. There, he dabbled in porcelain production, showcasing yet another skill. But his rapid ascent bred enemies. French Foreign Minister Étienne François de Choiseul whispered doubts to the king, and a warrant was issued. Slipping arrest, the Count fled to England, then vanished into Europe’s vast expanse.

A Wandering Legend and a Curious Death

For the next two decades, the Count roamed the continent under aliases like “Count Bellamare” and “Knight Schoening.” In 1779, he settled in Schleswig, near Denmark, befriending Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, an occult enthusiast enthralled by his alchemical feats—allegedly crafting flawless gems and merging stones into larger ones. For five years, he thrived in a custom lab, a sage-like figure to the prince. Then, on February 27, 1784, the impossible happened: the Count died. Or did he?

Within a year, reports surfaced of him at a Masonic convention in Paris, then meeting Catherine the Great in Russia. Sightings multiplied over centuries—India, the Czech Republic, even California’s Mount Shasta in 1930, where author Guy Ballard claimed he inspired a religious movement, “I AM.” Theosophists hailed him as an “ascended master,” akin to Buddha or Christ, some suggesting he’d been Francis Bacon or Christopher Columbus in past lives. The legend grew, but so did skepticism.

Man or Myth?

The Count of Saint-Germain was real—his presence in London, Paris, and beyond is documented. But immortality? That’s trickier. His linguistic prowess was impressive but exaggerated; Walpole noted he spoke several languages well, not all fluently. His historical tales dazzled, yet no records verify their depth beyond a sharp mind. His “miracles”—dyes, gems—fizzled under scrutiny, often revealed as sleight of hand. Voltaire’s praise was likely sarcastic, and Casanova, a fellow charlatan, pegged him as a liar.

So who was he? On his deathbed, he reportedly confessed to Prince Charles he was 88, born in 1691 as the son of Ferenc II Rákóczi, a Hungarian noble who’d hidden him as a child during a rebellion. It fits—explaining his education and mystery—but the timeline’s tight, and his lifelong deceit casts doubt. Was this final tale just another ruse?

Whether a conman or a genius, the Count’s legacy endures. He infiltrated Europe’s elite with no pedigree, dined with kings, and spun a story so wild it’s echoed for nearly 300 years. Immortal or not, his legend is—and that’s a feat few can claim.