In 2005, a remarkable tale unfolded on the lush, untamed island of Mindanao in the Philippines. Two elderly Japanese men, frail and disoriented, staggered out of the dense jungle. Identifying themselves as Yoshio Yamakawa, 87, and Suzuki Nakauchi, 85, they posed a startling question to bewildered onlookers: “Is the war over?†Astonishingly, they weren’t referring to a recent conflict but to World War II—a war that had ended 60 years earlier. The men claimed they had been hiding in the wilderness since the war’s final days, cut off from the world and oblivious to its conclusion.

Their story ignited a media frenzy in Japan. A representative from a veterans’ group promised the Japanese embassy in Manila that he would bring the pair to authorities for a long-overdue return home. But just as quickly as they appeared, Yamakawa and Nakauchi vanished. Wary of the spotlight, they slipped back into the jungle, leaving their tale unverified and shrouded in mystery. While their account remains unconfirmed, it echoes a broader, stranger-than-fiction phenomenon: Japanese soldiers who lingered in Asia’s jungles for decades, unaware that peace had come.

A Legacy of Isolation

How could anyone miss the end of a war that reshaped the globe? For most, the surrender of Japan in 1945 was a clear turning point, marked by Emperor Hirohito’s historic radio address. Yet, across Southeast Asia and the Pacific, thousands of Japanese soldiers never returned home. The answer lies in Japan’s wartime culture—a blend of fierce loyalty, imperial ambition, and a refusal to accept defeat.

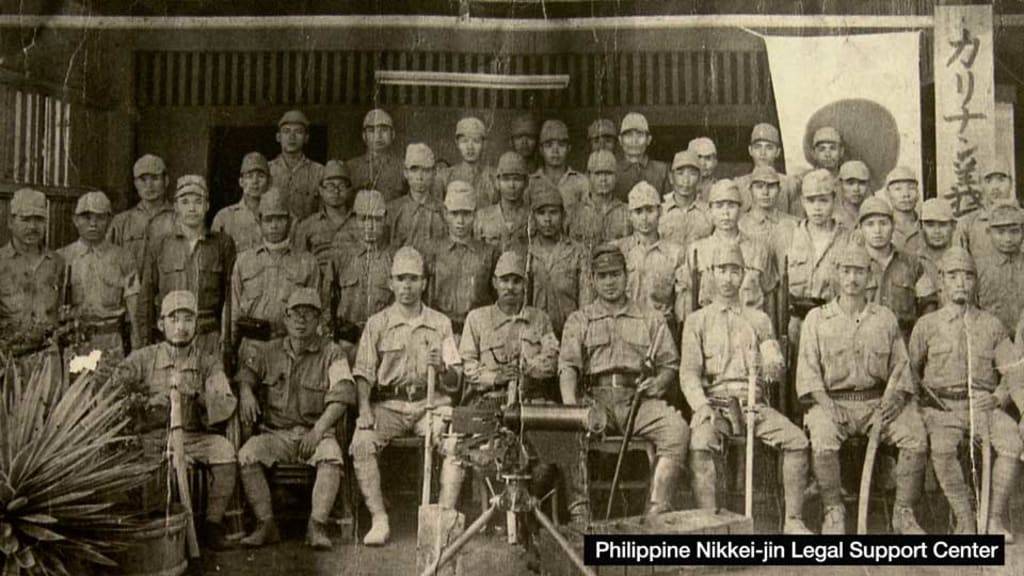

During World War II, Japan seized the chaos in Europe as a chance to expand its empire. With Western powers distracted, resource-rich colonies in Asia beckoned. Japan had already annexed Korea in 1910 and Manchuria in 1931, but its hunger for dominance grew. Promising to “liberate†Southeast Asia from colonial rule, Japan instead unleashed a campaign of conquest marked by shocking brutality—mass executions, civilian massacres, and atrocities that remain etched in history.

Japanese soldiers were driven by a code that equated surrender with dishonor. Fighting to the death was not just expected—it was sacred. Historian Nicholas Harling once noted that Europeans were “horrified by the violence, baffled by the determination, and impressed by the dedication†of Japan’s forces. This unyielding spirit, paired with rudimentary equipment, made them formidable despite their technological disadvantage against the Allies.

The War Ends-But Not for All

Japan’s imperial dreams crumbled in August 1945. On the 6th, an atomic bomb obliterated Hiroshima, followed by Nagasaki three days later. With over 200,000 civilians dead and two cities in ruins, Emperor Hirohito had no choice but to capitulate. On August 15, he addressed his people for the first time via radio. But his message was cryptic. Speaking in formal, classical Japanese—unfamiliar to many—he announced the “acceptance of the joint declaration of the powers†without explicitly saying “surrender.†For soldiers scattered across remote outposts, the news was muddled or outright unbelievable.

Compounding the confusion, Japan’s military demanded absolute obedience. Many troops, indoctrinated to fight until the end, dismissed the broadcast as propaganda or a trick. As a result, thousands turned into holdouts—guerrilla fighters hiding in jungles and mountains, clashing with locals and Allied forces long after the war’s official end on September 2, 1945.

Tales of Defiance and Survival

One such holdout was Captain Sakae Oba on Saipan. In 1944, as U.S. forces seized the Japanese-held island, Oba led 200 survivors—mostly civilians—into the jungle. For over a year, they waged a guerrilla campaign, ambushing American troops from the undergrowth. Even after Japan’s surrender, Oba refused to yield. It wasn’t until December 1945, when a former general convinced him the war was truly over, that he surrendered his sword. Returning to Japan, Oba later thrived as a businessman, living until 1992.

On the tiny island of Anatahan, 75 miles away, a different drama unfolded. In 1944, 30 Japanese soldiers swam ashore after their ship sank. Joined later by Kazuko Higa, the sole woman among them, they survived on coconuts and fish. But isolation bred chaos. Higa’s presence sparked jealousy, and the discovery of pistols from a crashed U.S. bomber turned rivalry into bloodshed. Over the years, 11 men died in a deadly cycle of murder over her affections, fueled by homemade coconut wine. U.S. leaflets announcing the war’s end were ignored until 1950, when Higa flagged down a passing ship. Letters from their families finally persuaded the survivors to return home in 1951.

The Lone Warriors

Decades later, solitary holdouts continued to emerge. In 1972, Shoichi Yokoi was found on Guam after 28 years in hiding. A soldier since 1943, he’d lived in a jungle burrow, eating lizards and refusing to surrender even after learning the war was over in 1952. Discovered by fishermen, he attacked them-paranoid after years alone-before being subdued. Back in Japan, Yokoi became a celebrity, joking that his survival stemmed from being “really good at hide and seek.†He died in 1997 at 82.

Perhaps the most infamous was Hiroo Onoda, who hid on Lubang Island in the Philippines until 1974. Ordered to disrupt Allied efforts in 1945, he outlasted his companions, dismissing all attempts to coax him out—leaflets, family photos, even search parties. Over the years, he killed 30 locals, believing the war raged on. In 1974, his former commander traveled to Lubang and personally ordered him to stand down. Onoda surrendered in his tattered uniform, later pardoned by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos. A hero in Japan, he ran survival schools until his death in 2014 at 91.

A Fading Echo

Today, few-if any—holdouts remain. Their stories, like that of Yamakawa and Nakauchi, blend fact with legend, offering a haunting glimpse into a time when loyalty defied reality. These men, lost to the world, fought a war that had long ended, driven by a code that refused to fade. Their legacy is a testament to both the resilience and the tragedy of human conviction.