On the night of December 10, 1987, in South Africa's Eastern Cape province, prison officers woke Mzolisi Dyasi in his cell. He was then driven on a bumpy ride to a hospital morgue, where he was asked to identify the bodies of his pregnant girlfriend, his cousin, and a fellow anti-apartheid fighter.

Read Also: Ghanaian journalist wins $18M in U.S. lawsuit against former MP

As he stood before the lifeless bodies of his loved ones, Dyasi fell to one knee, raised his fist in defiance, and tried to shout "Amandla!" ("power" in Zulu). But the word choked in his throat as he was utterly broken by the sight of them under the cold, harsh lights.

Reflecting on this moment, Dyasi told the BBC, "I was broken."

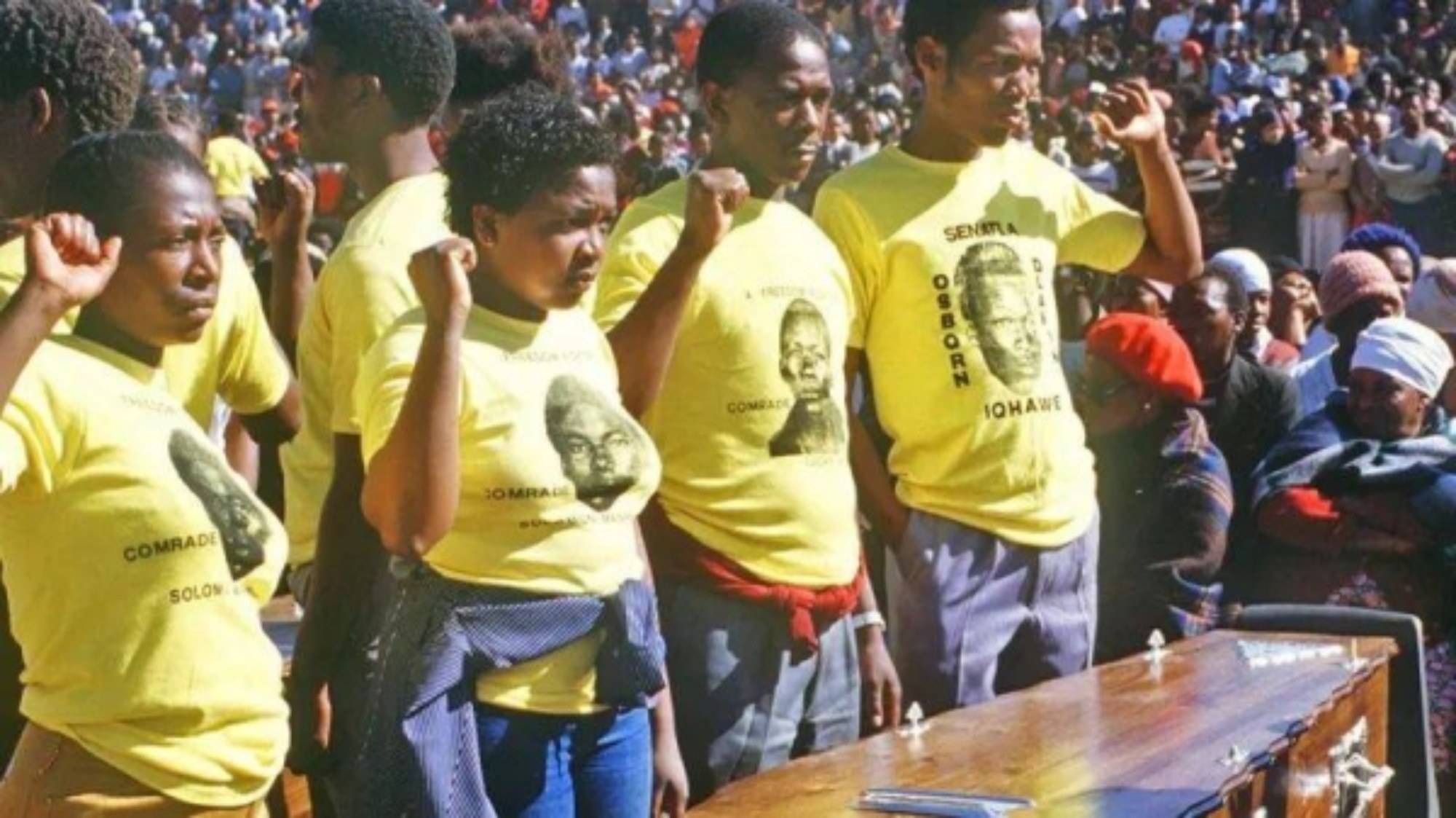

Now, four decades later, Dyasi still sleeps with the lights on, haunted by the mental and physical torture he endured during his four years in prison. His struggle to rebuild his life in a society he fought to change remains a heavy burden. As an underground operative for uMkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the then-banned African National Congress (ANC), Dyasi fought against the apartheid regime. In 1994, the ANC’s victory in South Africa’s first multiracial election marked the end of apartheid.

To uncover the atrocities of apartheid, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established, co-chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The government also set up a state reparations fund to assist victims of the regime. However, much of this fund has gone largely unspent.

Dyasi was one of about 17,000 people who received a one-time payment of 30,000 rand ($3,900; £2,400 at the time) in 2003. But, he says, that sum has done little to improve his situation. He had hoped to finish his university education but still hasn’t paid off the courses he took in 1997. Now in his 60s, Dyasi suffers from chronic health problems, struggling to afford medication with the meagre pension he receives for his role in the fight for freedom.

Professor Tshepo Madlingozi, a member of South Africa's Human Rights Commission, spoke to the BBC about the ongoing devastation caused by apartheid. He stressed that the impact wasn't just about the deaths and disappearances but also about locking people into generations of poverty. Despite the progress since 1994, many of the "born-free" generation—the young South Africans born after the end of apartheid—continue to inherit this cycle of hardship.

The reparations fund still holds around $110 million, but no one seems to know where it is or how it’s being used. Prof. Madlingozi voiced his concerns, asking, "What is the money being used for? Is it still there?"

The South African government did not respond to BBC's request for comment.

Lawyer Howard Varney, who has spent years representing victims of apartheid-era crimes, called the handling of reparations a "deep betrayal" of the families affected. He is currently representing a group of victims' families and survivors who are suing the government for $9 million, claiming the authorities failed to adequately address cases of political crimes that the now-disbanded TRC had highlighted for further investigation and prosecution.

Brian Mphahlele, a former prisoner, suffered from memory loss, a lingering result of the physical and psychological torture he endured at Cape Town’s notorious Pollsmoor Prison. Mphahlele, now deceased, received the 30,000 rand payout for his 10 years in prison but described it as an insult. "It went through my fingers. It went through everybody’s fingers. It was so little," the 68-year-old said in a phone interview from his home in Langa township, where he lived on a limited income. He had hoped the money would help him buy a house, but instead, he relied on soup kitchens three times a week.

Since his death, his dreams of a better life have gone unfulfilled.

Prof. Madlingozi reflected on how South Africa, after the end of apartheid, became a global symbol of racial reconciliation. However, he pointed out the unintended message it sent—that crimes against humanity could occur without consequences. Despite this, he remains hopeful, believing South Africa still has the opportunity to right its wrongs, even 30 years into democracy.

Dyasi, who left prison in 1990 after the unbanning of the ANC and the start of negotiations that led to Nelson Mandela’s presidency, still recalls the optimism and sense of freedom he felt at the time. But today, he is far from proud of the country he fought for. His disappointment echoes among many who struggled alongside him.

"We don’t want to be millionaires," Dyasi says. "But if the government could just look at the healthcare of these people if it could look after their livelihood, involve them in the economic system of the country."

He continues, "There were children orphaned by the struggle. Some of them want to go to school, but they still can't. Some people are homeless."

"Some people will ask, 'You were in prison, you were shot at. But what can you show for it?'"

Source: BBC News

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!