Lucius Apuleius’s The Golden Ass, also known as Metamorphoses, stands as a remarkable artifact of 2nd-century Roman literature, often hailed as one of the earliest surviving novels in Western tradition. Written around 150 A.D., this work weaves together a tapestry of bawdy tales, magical transformations, and profound spiritual themes, offering readers a lens into the complexities of Roman society and the human condition. Through the misadventures of its protagonist, Lucius, who is transformed into a donkey, Apuleius delivers a narrative that is equal parts satire, adventure, and allegory, culminating in a powerful exploration of redemption through the worship of the Egyptian goddess Isis. This article delves into the key elements of The Golden Ass, drawing from its early chapters and later sections to highlight its enduring significance.

The novel begins with Lucius, a young man from Madaura, traveling to the town of Hypata in northern Greece. His journey quickly takes a dark turn as he encounters Aristomenes, a honey-buyer who shares a chilling tale of witchcraft in Hypata. Aristomenes recounts how his friend Socrates was killed by the witch Meroe, who cut out his heart after he rejected her advances. This story serves as a warning to Lucius, but his curiosity and recklessness drive him forward. In Hypata, he stays with Milo, a miserly money-lender, and his wife Pamphile, a dabbler in magic. Despite further warnings from his cousin Byrrhaena, Lucius becomes entangled in a romance with Pamphile’s slave girl, Fotis, setting the stage for his eventual transformation.

The early chapters of The Golden Ass are marked by a blend of humor and danger, exemplified during the Festival of Laughter in Hypata. At a banquet hosted by Byrrhaena, Lucius hears the tale of Thelyphron, a man who lost his nose and ears while guarding a corpse from witches. This eerie story underscores the pervasive presence of magic in Hypata, a theme that soon engulfs Lucius himself. Returning to Milo’s house, Lucius kills three apparent brigands, only to be put on trial for murder. The trial, held during the festival, reveals the “brigands†to be enchanted wine-skins, a prank orchestrated by Pamphile’s magic. The public humiliation Lucius endures highlights Apuleius’s satirical take on human folly, as the townspeople laugh at Lucius’s expense.

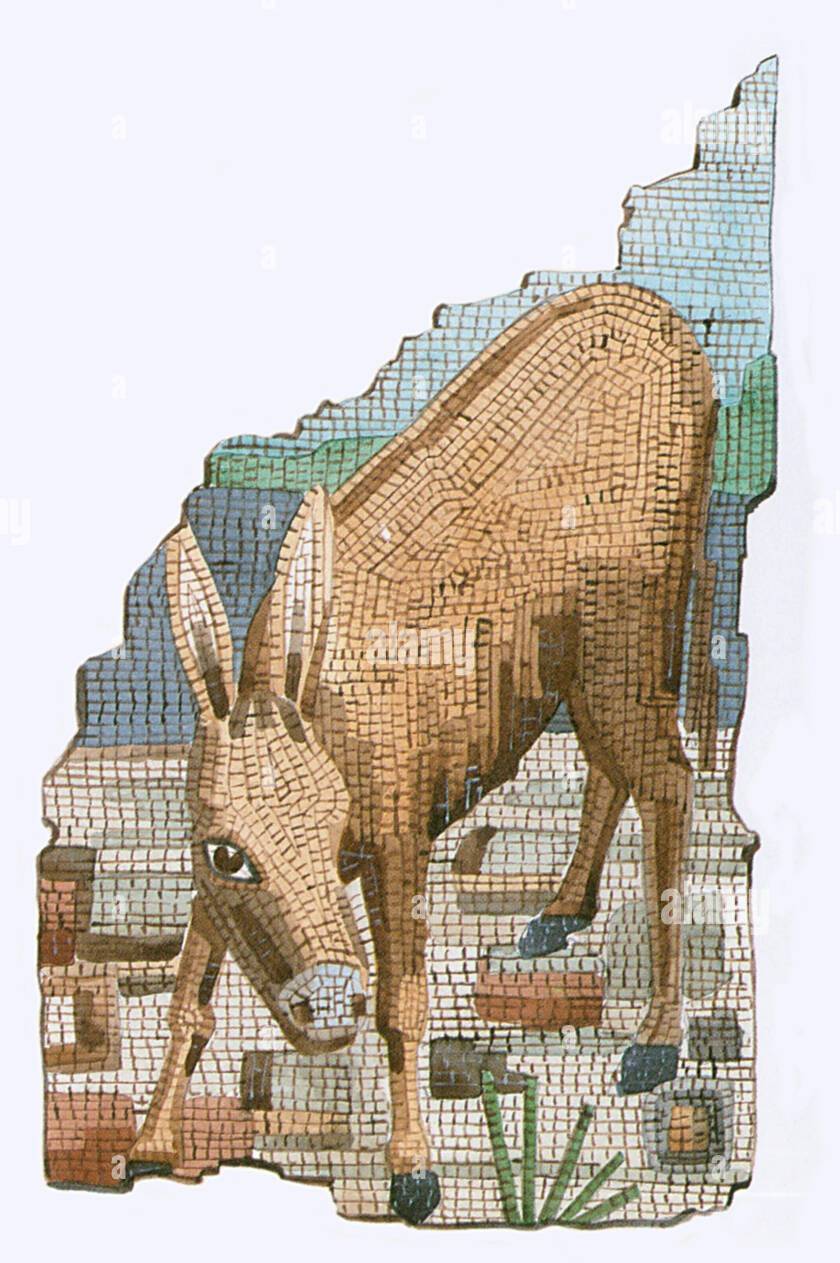

Lucius’s fascination with magic leads him to witness Pamphile transform into an owl, a bird associated with wisdom. Eager to experience such a transformation, he begs Fotis to use Pamphile’s drugs on him. However, Fotis, feeling used by Lucius, sabotages the ritual, turning him into a donkey-the animal most despised by the goddess Isis. Fotis promises to restore him with roses the next day, but before she can, thieves invade Milo’s house, taking Lucius to a cave where they hold a young woman named Charite hostage. In the cave, an old hag comforts Charite by telling the famous tale of Cupid and Psyche, a story that serves as a narrative within the larger novel.

The tale of Cupid and Psyche, which begins in these chapters, is a philosophical allegory about the soul’s journey toward divine love. Psyche, a mortal whose beauty rivals that of Venus, is targeted by the goddess for destruction. Venus sends her son Cupid to ruin Psyche, but he falls in love with her instead, whisking her away to a secret palace where he visits her under the cover of darkness. Psyche, curious about her mysterious lover, lights a candle to see him, revealing Cupid. He abandons her, and her subsequent trials-sorting grain, fleecing golden sheep, fetching water from the River Styx, and retrieving Proserpina’s beauty-symbolize the soul’s purification. With help from nature and divine forces, Psyche overcomes these challenges, eventually reuniting with Cupid in a union that represents the merging of Love and the Rational Soul.

Meanwhile, Lucius’s life as a donkey is one of suffering and degradation. He is passed from one owner to another, each more corrupt than the last. A band of eunuch priests buys him but is imprisoned for theft. A miller, his next owner, is killed by his adulterous wife, who then disappears. Lucius is stolen by a Roman soldier and sold to a nobleman named Thyasus, who plans to exhibit him in degrading gladiatorial shows. These episodes expose the darker side of human nature-greed, lust, and cruelty-seen through Lucius’s animal perspective, reinforcing Apuleius’s critique of Roman society.

The novel’s tone shifts in its final chapters, as Lucius’s journey takes a spiritual turn. He escapes his captors, bathes seven times in the sea, and prays to the “Blessed Queen of Heaven,†the goddess Isis. She appears to him, guiding him to her mystery rites, where he is transformed back into a human after a year as a donkey. Lucius then travels to Rome, embracing the worship of Isis and her consort Osiris, whom he acknowledges as the “Lord of all Gods†and “Queen of all feminine deities.†This spiritual awakening elevates Lucius to the “highest spiritual state possible to a mortal,†contrasting sharply with his earlier degradation.

The Golden Ass is a multifaceted work that defies easy categorization. Its early chapters revel in humor and satire, poking fun at human vanity and societal norms, while the embedded tale of Cupid and Psyche offers a profound allegory for the soul’s redemption. Lucius’s transformation into a donkey symbolizes his descent into a bestial state, reflecting his initial recklessness, while his eventual salvation through Isis reflects the growing popularity of her mystery cult in the Roman Empire. Apuleius’s iconoclastic view of humanity, seen through Lucius’s animal eyes, critiques the vices of his time, making the novel a timeless exploration of morality, spirituality, and the human condition. Even today, The Golden Ass remains a compelling read, its blend of magic, humor, and redemption offering insights into the complexities of life in the ancient world and beyond.