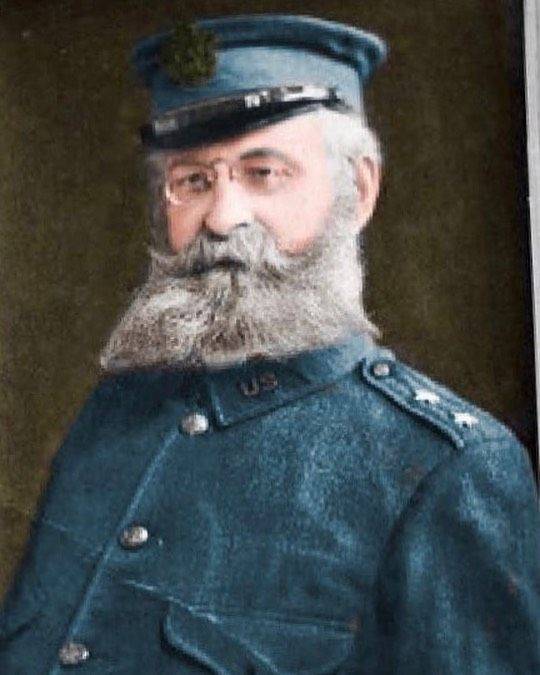

Imagine a world where survival isn’t just a buzzword but a daily, bone-chilling reality. That’s where Adolphus Greely lived-a man whose name might not ring bells like Columbus or Armstrong, but whose story is every bit as gripping. Born in 1844 in Newburyport, Massachusetts, Greely wasn’t the kind of guy who’d settle for a quiet life. He was a soldier, an explorer, and, later, a scholar, but above all, he was a survivor. His tale, especially that brutal Arctic expedition in the 1880s, is one of grit, desperation, and the kind of leadership that doesn’t crack even when the ice does.

Greely’s early years didn’t scream “future polar legend.†He grew up in a working-class family, joined the Union Army at 17 during the Civil War, and fought in some nasty battles-think Shiloh and Antietam. He wasn’t a glory hound; he was just steady, the kind of guy who’d keep his head when bullets flew. After the war, he stuck with the military, joining the Signal Corps in 1867. Back then, the Signal Corps wasn’t just about telegraphs—it was about pushing boundaries, like setting up weather stations in places no one sane would go. That’s where Greely’s path took a sharp turn toward the frozen unknown.

In 1881, the U.S. jumped into the International Polar Year, a global effort to study the Arctic. Greely, now a lieutenant, got tapped to lead an expedition to Lady Franklin Bay, way up in what’s now Nunavut, Canada. The plan? Set up a base, collect weather data, and maybe push farther north than anyone had before. Simple, right? Except the Arctic doesn’t do simple. Greely and his 25-man crew-soldiers and scientists, not exactly polar experts-sailed north on the Proteus, dropped off with supplies for a year, and waved goodbye to the ship. The idea was that a relief vessel would pick them up in 12 months. Spoiler: it didn’t.

For a while, things went okay. They built a camp called Fort Conger, ran their experiments, and even hit a new “farthest north†record at 83°24’N. Greely was no softie-he kept the team disciplined, logging data like clockwork. But by 1882, when no ship showed up, the cracks started forming. Supplies dwindled, and the second relief attempt in 1883 flopped too, thanks to storms and bad luck. Greely had a choice: sit tight and hope, or move. He chose to move, following orders to retreat south if help didn’t come. That decision kicked off one of the grimmest chapters in exploration history.

Picture this: 25 men, hauling sledges across cracking ice, with wind that’d freeze your soul. They aimed for Cape Sabine, 250 miles south, where supplies might be cached. It was August 1883, and the Arctic summer was fading fast. The journey was hell-boats capsized, food ran low, and the cold gnawed at them. By October, they’d made it to Cape Sabine, but the promised stockpile was a joke: some canned goods, a few scraps. Winter hit, and they were trapped in a makeshift camp, starving as temperatures plunged to minus 40.

Greely’s leadership got tested hard. He rationed what little they had—think 14 ounces of meat a day, then less, then nothing. Men started dying. Some went mad. There’s a dark rumor of cannibalism, and yeah, evidence later suggested a few resorted to it. Greely didn’t judge; he just kept order, writing in his journal with a hand that could barely grip the pen. By June 1884, when a rescue ship finally broke through, only six men were left alive, including Greely. They were skeletons, barely conscious, but he’d held them together through sheer will.

You’d think that’d break a guy, right? Not Greely. He came home a hero—got a Medal of Honor in 1935, long after the fact-and threw himself into work. He ran the Signal Corps, helped wire up the U.S. with telegraph lines, and even founded the National Geographic Society. The Arctic didn’t define him; it was just one insane chapter. He wrote books, too-stuff like Three Years of Arctic Service, where he laid out the ordeal plain and raw. No fluff, just facts and a quiet pride in what his team endured.

Greely wasn’t perfect. Critics say he was too rigid, that staying at Fort Conger might’ve saved more lives. Maybe. But the guy was following orders in a place where orders didn’t account for blizzards or botched resupply missions. He wasn’t a saint or a monster-just a man who faced the worst and didn’t blink.

He lived to 91, dying in 1935, and left a legacy that’s half legend, half cautionary tale. Today, you can find his name on maps-Greely Fiord, Fort Greely in Alaska-but his real mark is in the story. It’s about what happens when you’re pushed past the edge and keep going anyway. Adolphus Greely didn’t conquer the Arctic; he survived it, and that’s more than most could say.