The Walls of Benin: The Great Wall of Nigeria

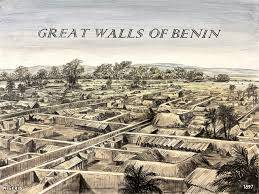

Long before European colonization reached West Africa, powerful and advanced civilizations flourished across the region. One such civilization was the Kingdom of Benin, located in what is now southern Nigeria, particularly in present-day Edo State. Among its many remarkable achievements, the most awe-inspiring was the construction of one of the largest and most impressive man-made structures in human history: The Walls of Benin, also known as the Benin Moat or Iya.

Origins and Purpose

The construction of the Walls of Benin is believed to have begun as early as 800 AD and continued over several centuries, especially peaking during the reign of Oba Ewuare the Great in the 15th century. The Oba (king) commissioned large-scale engineering projects, including the expansion of the wall system, as a way to strengthen the city’s defenses and consolidate his control over the kingdom.

The primary purpose of the walls was defensive—to protect the Benin Kingdom’s capital, Benin City, from external invasions and internal rebellions. The walls also served economic and social functions: regulating trade and movement in and out of the city, collecting tolls, and symbolizing the central power of the monarchy.

Scale and Structure

The Benin Walls were not just a single wall but a vast network of moats and ramparts, forming concentric rings around Benin City and its surrounding districts. The system covered an estimated 16,000 kilometers of earthworks, making it possibly the largest earthwork ever constructed prior to the modern era.

-

The inner wall protected the royal palace and central city.

-

The outer walls enclosed villages and farmlands, with gates and checkpoints.

-

The moats, which could be up to 20 meters wide and 8 meters deep, were dug entirely by hand using basic tools.

The walls were made of earth (a mixture of sand and clay), and builders used a method called “cut and placeâ€, which involved digging up soil to form a deep ditch and using the removed earth to build up a rampart or embankment. Over time, these walls became overgrown with vegetation, blending into the landscape but still serving their protective function.

A Marvel of Human Ingenuity

In terms of volume of earth moved, the Benin Walls rivaled or even exceeded the construction of the Great Wall of China. The British anthropologist Fred Pearce once described them as “the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet.†In fact, in 1995, the Guinness Book of Records recognized them as the longest earthworks in the world.

What makes the achievement even more astonishing is that it was constructed without modern machinery. The wall-building project would have required hundreds of thousands of workers and generations of coordinated effort.

Colonial Destruction and Legacy

Unfortunately, much of the structure was destroyed or damaged during the British invasion of Benin in 1897, when British forces looted and burned Benin City, dismantling the royal palace and taking sacred artworks (now scattered across European museums). Large parts of the walls were flattened to make way for colonial roads, and urbanization in the 20th and 21st centuries has continued to erode what remains.

Despite this, portions of the walls still exist today, buried beneath modern neighborhoods or standing as remnants in rural areas. Efforts have been made to preserve them, and the walls are currently on UNESCO’s tentative list for World Heritage status.

Cultural Significance

Beyond their physical scale, the Walls of Benin represent a symbol of African ingenuity, governance, and engineering prowess. They challenge common narratives that portray precolonial Africa as technologically backward. The walls reflect the organizational ability of the Benin Kingdom, its skilled labor force, and its commitment to security, identity, and heritage.

Today, they stand as a reminder of what once was—a lost world of kings, artisans, and urban planners who built a fortress-city in the rainforests of Nigeria long before contact with the Western world.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!