The Day the World Stood Still

Imagine you’re sitting in a bustling diner, the kind with checkered floors and the smell of coffee lingering in the air. It’s November 22, 1963, and the radio crackles with the usual chatter—until it doesn’t. A voice cuts through, trembling, announcing that President John F. Kennedy has been shot in Dallas. The world freezes. Forks clatter against plates. A waitress gasps, her tray wobbling. That’s the moment history cracked open, and we’re still piecing it together. How does one day, one bullet, ripple through time like that?

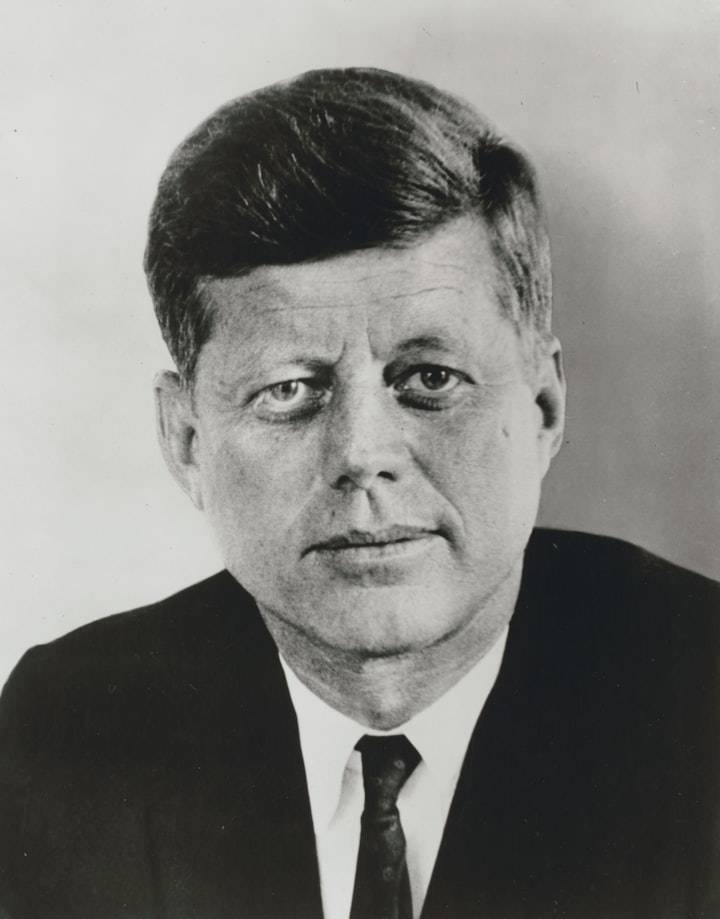

I’ve always been fascinated by moments that reshape everything, you know? The assassination of JFK isn’t just a historical event—it’s a wound that never quite healed. There’s this raw, human ache when you think about it. A young president, vibrant and flawed, struck down in broad daylight. It’s not just the loss of a leader; it’s the theft of a dream, a promise of what could’ve been. I get this pang of curiosity mixed with dread every time I dive into the details. What really happened that day? And why does it still haunt us?

Let’s walk through it. Picture Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Texas. The sun’s out, the crowd’s cheering, and Kennedy’s in an open-top Lincoln Continental, waving alongside Jackie, her pink suit impossibly bright. Then, shots—sharp, like firecrackers. Three, maybe two, depending on who you ask. The Zapruder film, that grainy 26-second reel, captures it all: the president slumping, Jackie scrambling, the chaos erupting. It’s raw, unfiltered, like watching a nightmare unfold in real time. I remember watching it for the first time, my stomach twisting. You can’t unsee it.

The official story, laid out by the Warren Commission, says Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. A troubled ex-Marine, perched in the Texas School Book Depository, firing a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle. Three shots, one fatal. Case closed. But here’s where it gets messy—human nature doesn’t like tidy endings. People started whispering. Why did Oswald, a man with shaky aim, pull off such a precise hit? Why was he gunned down by Jack Ruby two days later, before he could talk? And those witnesses—some swearing they heard shots from the grassy knoll, others claiming they saw men in suits vanishing into the crowd. It’s like a puzzle with half the pieces missing.

I think about my uncle, who was a teenager in ‘63, telling me how he sat glued to the black-and-white TV, watching Walter Cronkite choke up as he confirmed Kennedy’s death. “It felt like the world broke,†he said. That’s not just a story; it’s a glimpse into how deeply this cut. People didn’t just mourn a president—they mourned hope. The Camelot myth, that shining vision of a new America, crumbled in Dallas. And yet, the grief sparked something else: questions. Theories. A hunger for truth that’s never really faded.

Now, let’s be real—conspiracy theories are a rabbit hole. The CIA, the Mafia, the Soviets, even rogue elements in the U.S. government—people have pointed fingers everywhere. Some say the Warren Commission was a rushed cover-up; others swear by its findings. I’m not here to sell you on one side or the other. I’m just… curious. Like, how do you make sense of the “magic bullet†theory, where one shot supposedly zigzagged through Kennedy and Governor Connally? It’s wild to think about. And the fact that files are still classified, even now, in 2025? That’s enough to make anyone raise an eyebrow.

But here’s a thought that sticks with me: maybe it’s not about the answers. Maybe it’s about what this moment says about us. I was at a coffee shop last week, overhearing two guys debating JFK’s death like it happened yesterday. One was convinced it was a government job; the other just shrugged and said, “We’ll never know.†That’s the thing—it’s not just history. It’s personal. It’s your neighbor, your uncle, your friend, all grappling with the same questions. It’s human to want clarity, to chase the truth, even when it’s slippery.

The assassination reshaped America. It fueled distrust in institutions, sparked a wave of activism, and changed how we protect our leaders. Before Dallas, presidents rode in open cars. After? Bulletproof limos and Secret Service everywhere. It’s a small detail, but it hits me hard—how one moment can rewrite the rules. I wonder what Kennedy would think, looking at us now, still arguing, still searching.

So, where does that leave us? I don’t have a neat bow to tie this up with. The truth about November 22, 1963, might be buried in those sealed files, or maybe it’s lost forever. But I keep coming back to that diner, those stunned faces, that collective gasp. It reminds me how fragile our moments are, how quickly everything can change. What do you think—can we ever really know what happened? Or is the search itself what keeps us human?