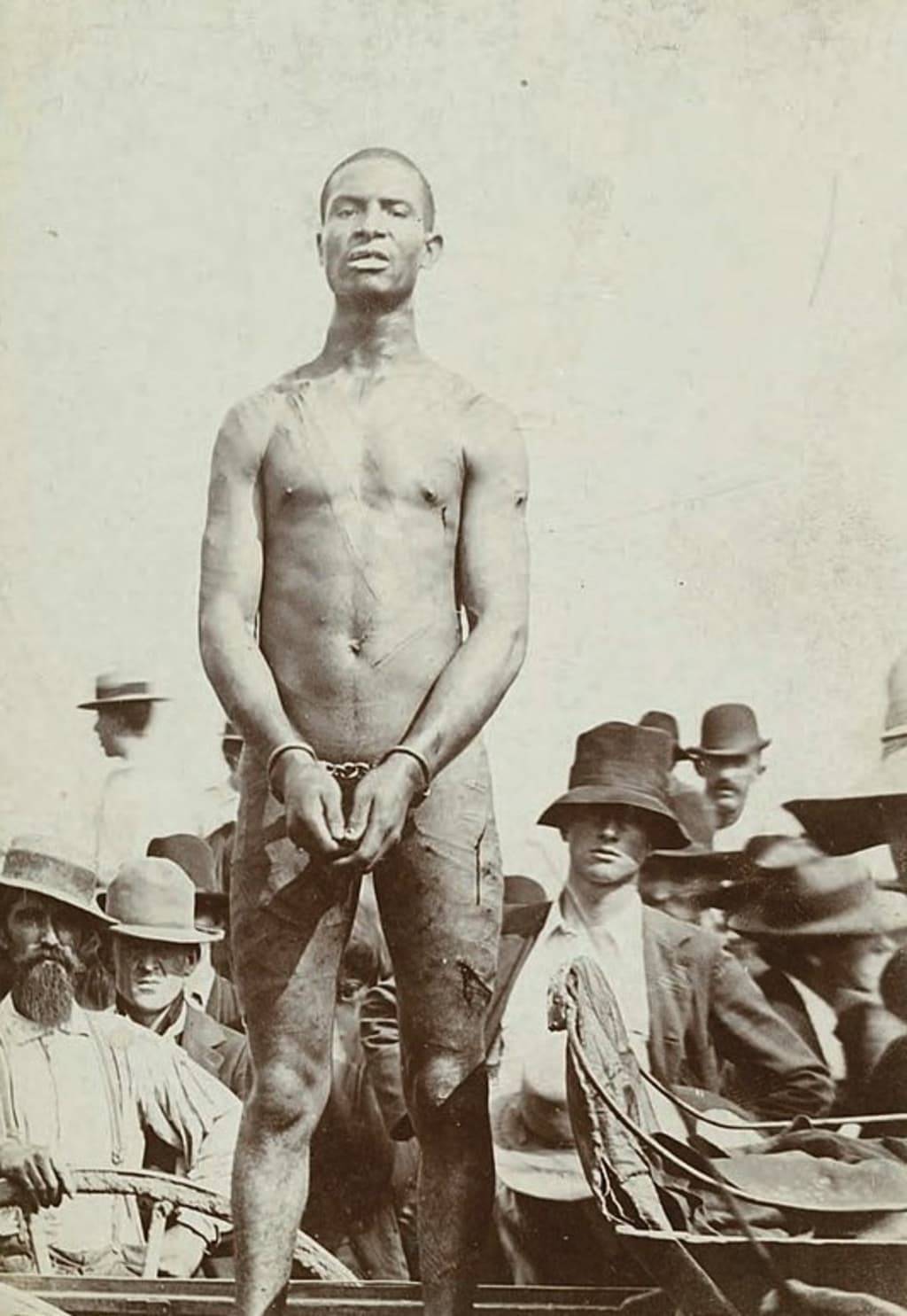

Imagine a young man, barely 19, standing in the scorching Missouri sun, his wrists bound, his body stripped bare. The air is thick with the shouts of a crowd-over a thousand strong-their faces twisted with rage. This isn’t a scene from a movie. This was Frank Embree’s reality on July 22, 1899, in Fayette, Missouri. His story, one of unimaginable cruelty, pulls you in and forces you to look at a truth so raw it stings. How does a single moment of injustice echo through generations? Let me take you there.

I first stumbled across Frank’s story late one night, scrolling through old articles, the kind that make your stomach turn and your heart ache. There’s something about history-real history, not the polished version-that grabs you by the collar and demands you pay attention. Frank Embree’s life ended in a way that’s hard to fathom, but it’s a story we need to hear, to feel, to carry. It’s not just about one man; it’s about a nation wrestling with its past, and maybe, just maybe, its future.

Frank was a Black man from Garnett, Kansas, visiting his uncle in Howard County when everything unraveled. On June 17, 1899, a 14-year-old white girl, Willie Dougherty, was assaulted while riding to a friend’s house. The attacker rode a horse owned by Frank’s uncle, John Collins, and that was enough to pin the blame on Frank. No questions, no trial—just a name and a mob ready to act. Can you imagine the terror? Knowing you’re innocent, but the world’s already decided your guilt?

Frank fled to Kansas, hoping to escape the growing storm. But the reward for his capture-$300, split between the sheriff and the governor-was too tempting. He was caught, hauled back to Missouri, and locked up. The newspapers fanned the flames, calling him “the black brute†or “the fiend.†They didn’t see a man; they saw a target. And the mob? They weren’t waiting for a judge. On the morning of his trial, they stormed the wagon carrying him, dragged him to the spot where the assault supposedly happened, and began their torture.

They stripped him naked, whipped him with a bullwhip-103 lashes, to be exact. Each crack of the whip tore into his skin, and still, Frank insisted he was innocent. You know that moment when pain becomes so unbearable you’d say anything to make it stop? That’s what they wanted. After 103 lashes, Frank screamed, begging them to kill him quickly rather than prolong the agony. He gave them the confession they demanded, not because it was true, but because he was human, broken by torment. And then they hanged him, right there, in front of a cheering crowd. They took photos, turned them into postcards, and passed them around like souvenirs. Postcards. Of a man’s suffering.

What gets me, what really sticks, is that the assaults on white girls in the area didn’t stop after Frank’s death. That alone screams his innocence louder than any confession ever could. But back then, truth didn’t matter. The mob wanted blood, and they got it. No one was arrested, despite those clear photographs showing the faces of the lynchers. Not a single soul faced justice for Frank’s murder. Doesn’t that make you pause? How does a whole town watch a man die and just… move on?

I think about Frank’s last moments a lot. Did he think of his family? His home in Kansas? Did he pray for forgiveness for a crime he didn’t commit, or for the souls of those who judged him by his skin? There’s a filmmaker, Skinner Myers, who felt Frank’s story so deeply he made a short film about it, shot on 35mm to capture the weight of it all. Myers wrote about locking eyes with Frank’s photo, feeling the man’s pain across a century. That’s the kind of connection history demands from us-not just reading, but feeling.

This isn’t “critical race theory†or some academic debate. This is a man’s life, stolen in broad daylight. It’s a wound in our nation’s story, one we can’t keep ignoring. And yet, there’s a strange hope in telling it. By remembering Frank, by saying his name, we refuse to let him be forgotten. We refuse to let the truth be buried under excuses or denial.

So where does that leave us? I don’t have all the answers, but I know this: stories like Frank’s aren’t just history lessons. They’re a mirror. They ask us who we are, who we want to be. Are we brave enough to face the past, to call out its wrongs, and to build something better? Or do we turn away, hoping the pain stays buried? I think about Frank’s eyes in those photographs, staring back at us, daring us to answer. What do you see when you look at him?

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!