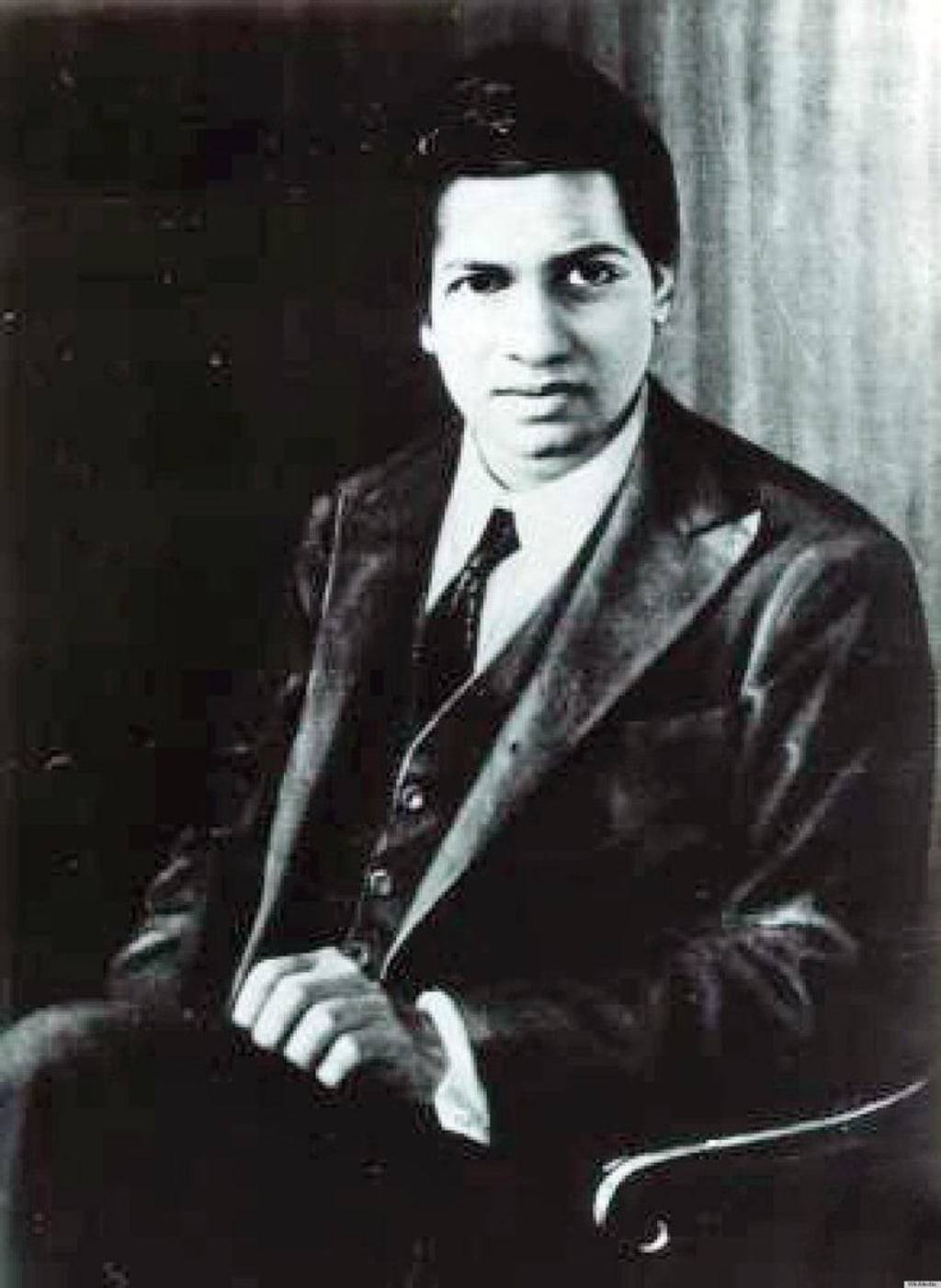

You know that feeling when a letter arrives, and it’s not just any letter, but one that changes everything? That’s what happened to Godfrey Harold Hardy, a mathematician tucked away in the quiet halls of Cambridge, when a worn envelope from India landed on his desk in 1913. It was from a young man named Srinivasa Ramanujan, a name that would soon echo through the ages. A poor clerk, no university degree, just a handful of formulas scratched out in desperation and brilliance. And those formulas? They weren’t just numbers-they were the kind of equations that made Hardy, a man who’d seen it all, stop and stare. This is the story of Ramanujan, a genius who saw math as a gift from the gods, a man whose life was as heartbreaking as it was extraordinary. A quick note before we dive in: this story touches on depression and attempted suicide. If you’re struggling, please don’t hesitate to reach out for help.

Imagine being a kid in a small town in India, where the air hums with the weight of tradition, and your family, though respected, scrapes by on next to nothing. That was Srinivasa Ramanujan’s world. Born into a Brahmin family-the highest caste in India’s ancient hierarchy-he grew up in Kumbakonam, a place where faith and ritual shaped every moment. His parents, devout Hindus, lived modestly, as their caste demanded. No flashy displays of wealth, just a quiet devotion to spiritual depth. To make ends meet, they rented out rooms to subtenants, their home a revolving door of strangers.

Ramanujan, though? He was different. A quiet boy, happiest alone, lost in his thoughts. School was a battleground. He hated the rigid structure, the teachers barking orders. He’d skip classes, forcing his family to enlist a local police officer just to drag him to school. Can you imagine? A kid so stubborn he needed an escort to class? But when they finally settled in Kumbakonam, something clicked. Math became his refuge. By 13, he was outpacing his classmates, breezing through exams, even stumping his teachers with questions like, “If you divide zero by zero, is it still one?” The boy wasn’t just clever-he was relentless.

A Spark Ignites

At 16, Ramanujan stumbled across a book that changed everything. Not a novel, not a story, but a dense, dusty tome of 5,000 equations and theorems, thrown together with barely any explanation. It was called A Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics by George Shoobridge Carr, meant for students cramming for exams. To most, it was a slog. To Ramanujan? It was a treasure map. He dove into its pages, solving equations like puzzles, crafting his own proofs in ways no textbook would ever teach. And here’s the thing: he didn’t just see numbers. He saw divinity. To him, every equation was a whisper from the gods, a glimpse into the universe’s hidden machinery. “An equation for me has no meaning,” he once said, “unless it expresses a thought of God.”

His faith wasn’t just tradition-it was personal. He prayed to Namagiri, his family’s goddess, and believed his talent flowed from her. That conviction drove him, but it also set him apart. While his peers chased grades, Ramanujan chased truth. He rediscovered solutions to centuries-old problems, like the quadratic equation, without ever knowing they’d been solved before. By the time he finished school, he was a local legend, earning a scholarship to college. But college? That’s where the cracks started to show.

The Weight of Genius

College demanded balance-history, literature, science-but Ramanujan only cared about math. While professors droned on about Roman empires, he scribbled formulas, lost in a world of infinite series and algebraic transformations. It cost him. He lost his scholarship, and his family, already stretched thin, poured their meager savings into his education. The guilt gnawed at him. He was their prodigy, their hope, but also their burden. By 18, he dropped out. A second college attempt failed too. By his early 20s, Ramanujan was adrift, a genius with no place to land.

He married at 22, to a girl named Janaki, just 9 years old at the time-an arranged marriage that wouldn’t truly begin until she was older. The pressure to provide only grew heavier. He carried his notebooks everywhere, pages packed with equations, written in green ink, theorems neatly numbered at first, then spilling into chaotic scribbles as inspiration outran paper. Those notebooks were his lifeline, his proof of worth. He showed them to anyone who might listen, hoping for a chance.

Finally, someone did. The Indian Mathematical Society in Pune saw his potential and offered support. Ramanujan published his first paper on Bernoulli numbers, a sequence that danced through infinite sums. But the modest salary wasn’t enough. He worked as a clerk in Madras, scraping by, his brilliance still unseen by the world. His friends urged him to write to Western mathematicians. He tried, but most ignored him. Until he wrote to G.H. Hardy.

A Letter Across the Sea

Hardy was a Cambridge star, a man who loved cricket as much as calculus, a skeptic who saw math as a human endeavour, not a divine one. When Ramanujan’s letter arrived, with its nine pages of equations, Hardy was skeptical too. A clerk from India, no degree, claiming to solve problems that baffled the greats? It sounded like a hoax. But those equations-they were strange, beautiful, impossible. One claimed the sum of all natural numbers was -1/12, a result so wild it seemed absurd, yet it held truth in the arcane depths of number theory. Hardy showed the letter to his colleague John Littlewood, and they pored over it late into the night. “These formulas must be true,” they concluded, “because no one would have the imagination to invent them.”

Hardy wrote back, thrilled but insistent: Ramanujan needed to provide proofs. Without them, his work couldn’t stand in the academic world. He invited Ramanujan to Cambridge, but there was a catch. As a devout Brahmin, Ramanujan couldn’t cross the sea without risking his caste, his family, his place in the world. His mother, his anchor, forbade it. Until one night, she dreamed of Namagiri, who told her to let her son go. With her blessing and a scholarship from Madras University, Ramanujan boarded a ship in 1914, bound for a world he couldn’t imagine.

Cambridge: A Dream and a Trial

London hit him like a storm. Five million people, a blur of noise and cold, so different from the warm, quiet streets of Madras. He struggled with forks, forgot English names, and waddled across Cambridge in slippers because Western shoes pinched his feet. But the math? That was home. Working with Hardy and Littlewood, Ramanujan finally had peers who understood his genius. They dove into his notebooks, marveling at his intuitive leaps. His formula for pi, for instance, was a revelation-calculating eight digits with a single term, where others needed millions. Even today, his work ripples through string theory and beyond.

But England was harsh. World War I erupted, emptying Cambridge of students. Littlewood left for the war effort, and Ramanujan grew isolated. The cold seeped into his bones, and food was a nightmare. As a Brahmin, he could only eat vegetarian meals prepared in specific ways, but wartime shortages left him with little more than rice and lemon juice. His health crumbled. Tuberculosis, or perhaps an intestinal disease, took hold. He moved from hospital to hospital, his body failing, his spirit fraying.

Hardy became his lifeline, a friend who pushed him to refine his work, to prove his genius to the world. But the pressure was crushing. Ramanujan craved Hardy’s approval, but the isolation, the illness, the distance from home-it was too much. One day in 1917, he stood on a London Underground platform and threw himself onto the tracks. A guard’s quick action saved him, and Hardy’s influence kept him out of jail. But the darkness lingered.

A Legacy Cut Short

In 1918, a flicker of light: Ramanujan was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, one of the youngest ever, joining the ranks of Newton and Darwin. He was overjoyed, but his body was failing. Madras University offered a fellowship, enough to return home. In 1919, he sailed back to India, reuniting with his wife, now 18, and his mother. But he wasn’t the same. Thin, withdrawn, a shadow of the cheerful boy he’d been. Doctors couldn’t save him. Even as he lay dying, he worked, scribbling mock theta functions-mysterious equations that puzzled mathematicians for decades.

On April 26, 1920, at just 32, Ramanujan slipped away, his wife feeding him diluted milk until the end. “His name will live for a hundred years,” he told her. And it has. His notebooks, still studied today, are a testament to a mind that saw the universe in numbers. But what haunts me is the what-if. What if he’d had better health, more time, a world that didn’t break him? Would we have unlocked more of infinity through his eyes?

What do you think-can genius ever truly thrive in a world that doesn’t know how to nurture it?

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!