It’s a dusty summer evening in 1872, and you’re sitting in a dimly lit Texas saloon. The air smells of whiskey and sweat, and behind the bar, a man named John St. Helen is reciting Shakespeare with a flourish that could make the room hush. His dark hair’s going gray at the edges, but there’s something magnetic about him-a lean frame, a quick draw of a pistol when he thinks no one’s watching. You lean closer, intrigued. Then, in a fevered whisper years later, he confesses something that makes your blood run cold: “I’m John Wilkes Booth.” Wait-what? The guy who killed Abraham Lincoln? The man history says was gunned down in a Virginia barn in 1865? My curiosity spiked, and I couldn’t stop wondering: could this be true? Could Booth have pulled off the greatest escape in American history?

Let’s dive into this mystery with a mix of excitement and skepticism, because, honestly, it’s one wild ride. The official story is burned into every history textbook: John Wilkes Booth, a famous actor and Confederate sympathizer, shot President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre, broke his leg leaping to the stage, and was killed 12 days later in a fiery barn showdown. Case closed, right? But then you stumble across whispers-missing diary pages, a mummified body touring carnivals, a Texas bartender with secrets. It’s enough to make you pause and think, What if history got it wrong?

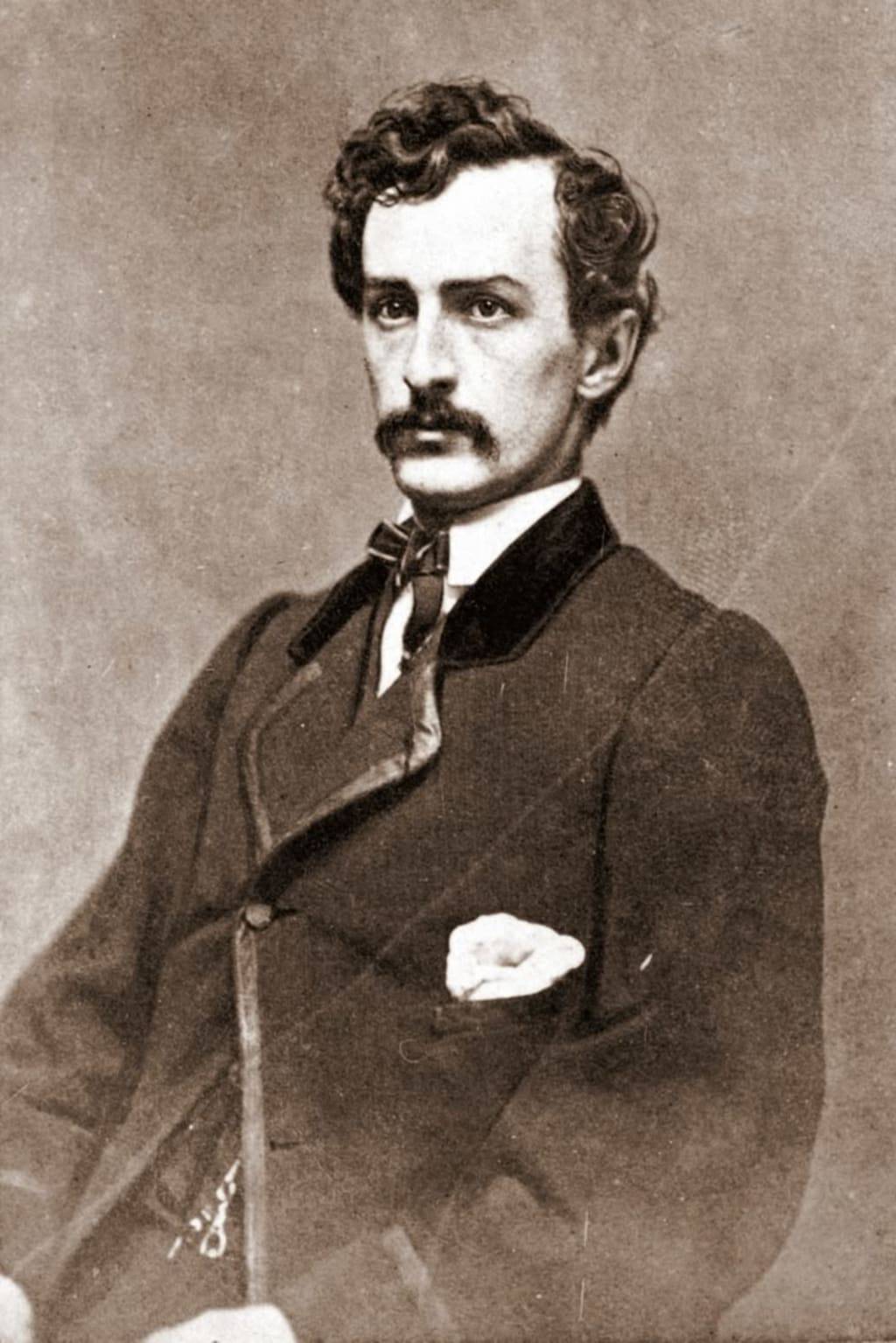

Booth was no ordinary assassin. He was a celebrity, the kind whose fans tore at his clothes. Dark hair, piercing eyes, a flair for Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar-he saw Lincoln as a tyrant, just like Caesar. As a Confederate spy, he moved in elite circles, gathering secrets from politicians and businessmen. When he learned of Lincoln’s plans to give land and voting rights to former slaves, Booth snapped. Kidnapping Lincoln was his first plan, a bold scheme to trade the president for Confederate prisoners. But when General Lee surrendered, that plan crumbled. Then, like a twist of fate, Booth overheard Lincoln would be at Ford’s Theatre. He knew that place like the back of his hand-every exit, every shadow. And here’s where it gets murky: some say he had help, not from Southern rebels, but from inside Lincoln’s own cabinet.

Enter Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War, a man with a iron grip on the military and a bone to pick with Lincoln’s leniency toward the South. The theory goes that Stanton wanted control, and Vice President Andrew Johnson was his puppet. Did Stanton feed Booth Lincoln’s schedule, escape routes, even funds? Did he clear the way by pulling Lincoln’s usual bodyguards? It’s a chilling thought. On April 14, 1865, Booth slipped into the presidential box, shot Lincoln during a burst of laughter, and vanished into the night. Stanton sealed every bridge out of Washington-except, curiously, the one Booth used. Coincidence? I’m not so sure.

Now, here’s where the story takes a turn into the bizarre. History says Booth and his accomplice David Herold fled to Virginia, hiding in swamps and barns until soldiers cornered them at Garrett’s farm. Herold surrendered, but the man in the barn-supposedly Booth-was shot through the neck. “Tell mother I die for my country,” he gasped, and that was that. Or was it? The autopsy was rushed, the body wrapped in a blanket, shuffled from wagon to tugboat to a secret burial. Witnesses, like Dr. John Frederick May, who’d once removed a tumor from Booth’s neck, hesitated. The scar was there, but the body? It didn’t feel right. The leg injury was on the wrong side, and it looked old, not fresh from Booth’s theater leap. Others swore the man’s face, his build, just wasn’t Booth.

And then there’s the diary-Booth’s diary, recovered from the barn, with 86 pages missing. FBI tests later confirmed those pages were torn out, filled with names and payments that could’ve pointed to a bigger plot. Stanton got that diary. It’s gone now. Destroyed, they say. I can’t help but wonder: what was in those pages? Names of powerful men? Proof of a conspiracy? It’s the kind of thing that keeps you up at night.

Fast-forward to that Texas saloon. John St. Helen, the mysterious bartender, befriends a young lawyer named Finis Bates. One night, sick with pneumonia, St. Helen grabs Bates and spills a jaw-dropping confession: he’s Booth, he escaped, and someone else died in that barn. He describes Ford’s Theatre in vivid detail-the creak of the stage, the sound of Lincoln’s last breath. Bates is floored. But when St. Helen recovers, he vanishes, leaving only an apron and a thousand questions.

Years later, in 1903, a painter named David E. George kills himself in Oklahoma, leaving a note: “Contact Finis Bates.” Bates arrives, pulls back the sheet, and swears it’s St. Helen-older, thinner, but unmistakable. The body is embalmed, and soon it’s a carnival attraction, a mummy billed as “John Wilkes Booth.” Crowds gawk. Doctors note a broken left leg, a scarred neck, a deformed thumb-all matching Booth. But here’s the kicker: DNA tests could settle this once and for all, yet every request to test the vertebrae from the barn autopsy or the mummy has been denied. Why? What’s being hidden?

There’s more. Booth’s secret wife, Izola Mills, and their children, Ogarita and Harry, surface in stories. A will signed “John Byron Wilkes” from India names them, along with other heirs. Ulysses S. Grant himself ordered a probe into this will-how could a stranger know Booth’s private life so intimately? Yet, the trail goes cold. The mummy disappears into storage, and the official story holds: Booth died in 1865.

But let’s pull this apart, because, you know, I’m a sucker for a good mystery. The escape theory is juicy-Booth swapping coats with a double, James William Boyd, a Confederate soldier with the same initials, released by Stanton himself. Boyd takes the bullet, Booth sails to India, then returns as St. Helen, then George. It’s cinematic, almost too perfect. But cracks appear. Bates, the lawyer, turned his story into a 1907 book, The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth, and made a fortune touring with that mummy. Handwriting from St. Helen? It didn’t match Booth’s. Izola’s descendants? Their DNA showed no link to the Booth family. And Booth’s 12-day flight after the assassination? Documented by witnesses at every turn—farmers, soldiers, sympathizers. Faking that would’ve been a magic trick.

Still, I can’t shake the what-ifs. The missing diary pages, the botched autopsy, the blocked DNA tests-it’s enough to make you squint at history and wonder. And here’s a bigger question: what if Lincoln had lived? His reconstruction plan was about healing, not punishment. Andrew Johnson, who took over, was a disaster-vetoing civil rights bills, letting the KKK rise. If Lincoln had served his full term, would America’s scars from slavery have healed differently? Would we live in a less divided nation today?

I lean toward believing Booth died in that barn, but the story’s too messy to be certain. The conspiracy theories, the mummy, the whispers of a cover-up-they pull you in because they let us play with history’s edges. They make us ask, What if the villain got away? More importantly, they make us mourn what was lost-Lincoln’s vision, a chance at a better America. Whether Booth burned in that barn or lived to pour whiskey in Texas, his shadow lingers. So, I’ll leave you with this: if Booth did escape, what does that say about the stories we’re told? And if he didn’t, why are we still chasing his ghost?

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!