Encyclopedia Britannica

Home

List

World History

Pablo Escobar: 8 Interesting Facts About the King of Cocaine

By Amy Tikkanen

The curation of this content is at the discretion of the author, and not necessarily reflective of the views of Encyclopaedia Britannica or its editorial staff. For the most accurate and up-to-date information, consult individual encyclopedia entries about the topics.

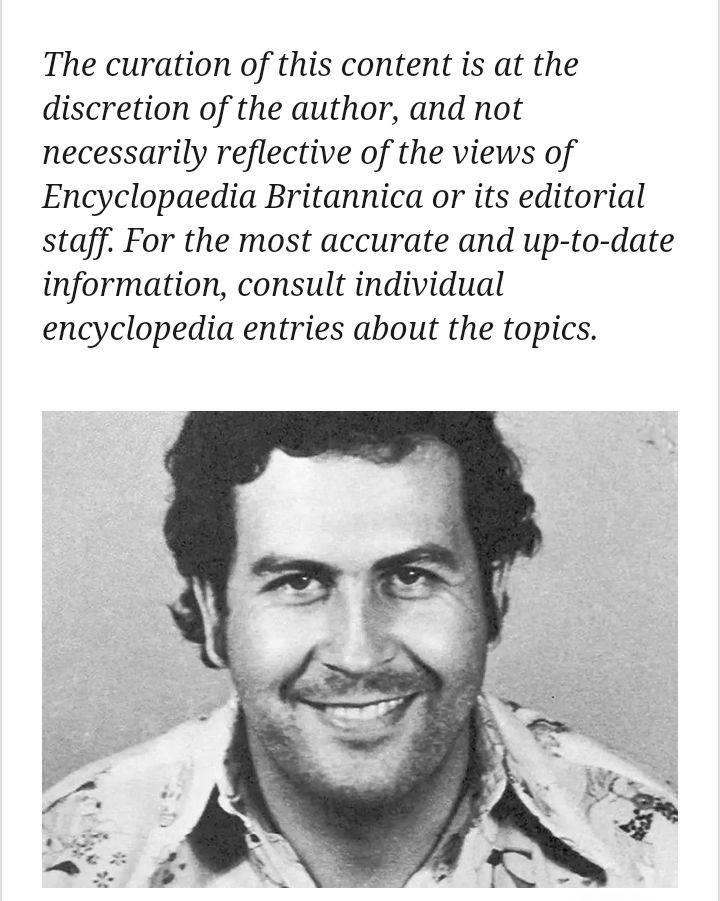

A mug shot taken by the regional Colombia control agency in Medellin

Colombian National Police

More than two decades after his death, Pablo Escobar remains as well known as he was during his heyday as the head of the Medellín drug cartel. His fixture in popular culture is largely thanks to countless books, movies, and songs. We’ve decided to make our contribution with a list of facts about the life of the larger-than-life Escobar.

Rise to Power

Escobar, the son of a farmer and a schoolteacher, began his life of crime while still a teenager. According to some reports, his first illegal scheme was selling fake diplomas. He then branched out into falsifying report cards before smuggling stereo equipment and stealing tombstones in order to resell them. Escobar also stole cars, and it was this offense that resulted in his first arrest, in 1974. Shortly thereafter, he became an established drug smuggler, and by the mid-1970s he had helped found the crime organization that evolved into the Medellín cartel.

Mucho Dinero

At the height of its power, the Medellín cartel dominated the cocaine trade, earning an estimated $420 million a week and making its leader one of the wealthiest people in the world. With a reported worth of $25 billion, Escobar had ample money to spend—and he did. His lavish lifestyle included private planes, luxurious homes (see below), and over-the-top parties. In the late 1980s he reportedly offered to pay off his country’s debt of $10 billion if he would be exempt from any extradition treaty. In addition, while his family was on the run in 1992–93, Escobar reportedly burned $2 million in order to keep his daughter warm. Despite his best efforts, however, even Escobar couldn’t spend all that money, and much of it was stored in warehouses and fields. According to his brother, about 10%, or $2.1 billion, was written off annually—eaten by rats or destroyed by the elements. In some cases, it was simply lost.

Hacienda Nápoles

Escobar owned a number of palatial homes, but his most-notable property was the 7,000-acre estate known as Hacienda Nápoles (named after Naples, Italy), located between Bogotá and Medellín. Reportedly costing $63 million, it included a soccer field, dinosaur statues, artificial lakes, a bullfighting arena, the charred remains of a classic car collection destroyed by a rival cartel, an airstrip, a tennis court, and a zoo (more on that later). The estate—the front gate of which is topped by the plane he used on his first drug run to the U.S.—was later looted by locals, and it is now a popular tourist attraction.

King of the Jungle

Escobar’s private zoo was home to some 200 animals, including elephants, ostriches, zebras, camels, and giraffes. Many of the creatures were smuggled into the country aboard Escobar’s drug planes. After his death in 1993, most of the animals were transferred to zoos. However, four hippopotamuses were left behind. They soon multiplied, and by 2016 upwards of 40 lived in the area. The potentially dangerous animals have damaged farms and inspired fear in locals. Authorities began castrating male hippos in an effort to control the population.

Robin Hood

Perhaps hoping to win the support of everyday Colombians, Escobar became known for his philanthropic efforts, which led to the nickname “Robin Hood.” He built hospitals, stadiums, and housing for the poor. He even sponsored local soccer teams. His popularity with many Colombians was demonstrated when he was elected to an alternate seat in the country’s Congress in 1982. Alas, two years later he was forced to resign after a campaign to expose his criminal activities. The justice minister who led the efforts was assassinated.

“Plata o Plomo”

Escobar’s way of handling problems was “plata o plomo,” meaning “silver” (bribes) or “lead” (bullets). While he preferred the former, he had no qualms about the latter option, earning a reputation for ruthlessness. He reportedly killed some 4,000 people, including numerous police officers and government officials. In 1989 the cartel was blamed for detonating a bomb on a plane that was carrying an alleged informant. Some 100 people died.

La Catedral

In 1991 Escobar offered to turn himself in to authorities—if he was allowed to build his own prison. Surprisingly—or perhaps not—Colombian officials agreed. The result was the luxurious La Catedral. Not only did the facility include a nightclub, a sauna, a waterfall, and a soccer field; it also had telephones, computers, and fax machines. However, after Escobar tortured and killed two cartel members at La Catedral, officials decided to move him to a less-accommodating prison. Before he could be transferred, however, Escobar escaped, in July 1992. And that brings us to…

The King Is Muerto

After his escape, the Colombian government—reportedly aided by U.S. officials and rival drug traffickers—launched a massive manhunt. On December 2, 1993, Escobar celebrated his 44th birthday, allegedly enjoying cake, wine, and marijuana. The next day, his hideout in Medellín was discovered. While Colombian forces stormed the building, Escobar and a bodyguard managed to get to the roof. A chase and gunfight ensued, and Escobar was fatally shot. Some, however, have speculated that Escobar took his own life. The drug lord, who faced possible extradition to the U.S. if arrested, had once said that he “would rather have a grave in Colombia than a jail cell in the U.S.”

Home

List

World History

7 Amazing Historical Sites in Africa

By Amy McKenna

The curation of this content is at the discretion of the author, and not necessarily reflective of the views of Encyclopaedia Britannica or its editorial staff. For the most accurate and up-to-date information, consult individual encyclopedia entries about the topics.

The African continent has long been inhabited and has some amazing historical sites to show for it. Check out these impressive examples of architecture, culture, and evolution.

Olduvai Gorge

Olduvai Gorge or Olduwai Gorge, Tanzania, Africa (eastern Serengeti Plain) Where fossil remains of more than 60 hominins provides the most continuous known record of human evolution. Mary Leakey and Louis Leakey made discoveries here. Archaeology

Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania

Photos.com/Jupiterimages

This paleoanthropological site is located in the eastern Serengeti Plain, within the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in northern Tanzania. Olduvai Gorge is remarkable for its deposits, which cover a time span from about 2.1 million to 15,000 years ago and have yielded the fossil remains of more than 60 hominins (human ancestors). It has provided the most continuous known record of human evolution during the past two million years. It has also produced the longest known archaeological record of the development of stone tool industries. The famous archaeologist and paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey discovered a skull fragment there in 1959 that belonged to an early hominin.

Thebes

Ancient Egyptian obelisk and statuary, Luxor, Egypt.

Temple of Luxor, Thebes, Egypt

© Goodshoot/Jupiterimages

Thebes is one of the famed cities of antiquity. Its remains, some of which date back to the 11th dynasty (2081–1939 BCE) of ancient Egypt, lie on both sides of the Nile River in what is now the modern-day country of Egypt. The Thebes area also includes the archaeologically rich sites of Luxor, the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, and Karnak. The remains found at these sites—including impressive temples, palaces, and royal tombs—provide a view of the architecture, religious customs, and daily life of ancient Egypt.

Leptis Magna

Libia. Leptis Magna. Teatro

Leptis Magna, Libya: Roman amphitheatre

© Massimo Cutrupi/Fotolia

Leptis Magna was the largest city of the ancient region of Tripolitania. It is located on the Mediterranean coast of what is now northwestern Libya and contains some of the world’s finest remains of Roman architecture. It was founded as early as the 7th century BCE by Phoenicians and was later settled by Carthaginians, probably at the end of the 6th century BCE. The city became an important Mediterranean and trans-Saharan trade center. Leptis Magna changed hands and eventually became one of the best-known cities of the Roman Empire. It flourished under the emperor Septimius Severus (193–211 CE) before later seeing some decline owing to regional conflict. It fell into ruin after it was conquered by Arabs in 642 CE and eventually became buried in sand, only to be uncovered in the early 20th century.

Meroe

The ruins of the ancient Kushitic city of Meroe lie on the east bank of the Nile River in what is now Sudan. The city was established in the 1st millennium BCE. It became the southern administrative center for the kingdom of Kush about 750 BCE and later became the capital. It began to decline after being invaded by Aksumite armies in the 4th century CE. The ruins were discovered in the 19th century, and excavations in the early 20th century revealed parts of the town. The pyramids, palaces, and temples of Meroe are stunning examples of the architecture and culture of the kingdom of Kush.

Great Zimbabwe

Aerial view of the ruins of Great Zimbabwe.

Great Zimbabwe: ruins

ZEFA

During the 11th to 15th century, Great Zimbabwe was the heart of a thriving trading empire that was based on cattle husbandry, agriculture, and the gold trade on the Indian Ocean coast. The extensive stone ruins of this African Iron Age city are located in the southeastern portion of the modern-day country of Zimbabwe. It is thought that the central ruins and surrounding valley supported a Shona population of 10,000 to 20,000 people. The site is known for its stonework and other evidence of an advanced culture. Because of that, it was incorrectly attributed to various ancient civilizations such as the Phoenicians, the Greeks, or the Egyptians. Those claims were refuted when the English archaeologist and anthropologist David Randall-MacIver concluded in 1905 that the ruins were medieval and of exclusively African origin. His conclusions were later confirmed by another English archaeologist, Gertrude Caton-Thompson, in 1929.

Rock-hewn churches of Lalībela

Lalibela. House of Giorgis (Church of Saint George) rock church in Lalibela, Ethiopia. One of eleven churches arranged in two main groups, connected by subterranean passageways. A UNESCO World Heritage site.

House of Giorgis church, Lalībela, Ethiopia

© Top Photo Group/Thinkstock

Lalībela, located in north-central Ethiopia, is famous for its rock-hewn churches, which date back to the late 12th and early 13th centuries. The 11 churches, important in Ethiopian Christian tradition, were built during the reign of the Emperor Lalībela. The churches are arranged in two main groups, connected by subterranean passageways. Notable among the 11 churches are House of Medhane Alem (“Saviour of the World”), the largest church; House of Golgotha, which contains Lalībela’s tomb; and House of Mariam, which is noted for its frescoes. Centuries after they were built, the churches still draw thousands of pilgrims around important holy days.

Timbuktu

Courtyard of the Djingareiber mosque , Timbuktu

Timbuktu, Mali: Djinguereber mosque

KaTeznik

Located on the southern edge of the Sahara in what is now Mali, the city of Timbuktu has historical significance for being a trading post on the trans-Saharan caravan route and as a center of Islamic culture in the 15th through the 17th century. The city was founded by Tuaregs around 1100 CE, later became part of the Mali Empire, and then changed hands several times after that. Three of western Africa’s oldest mosques—Djinguereber (Djingareyber), Sankore, and Sidi Yahia—were built there during the 14th and early 15th centuries; Djinguereber was commissioned by the famed Mali emperor Mūsā I. The city was a center of Islamic learning and housed a large collection of historical African and Arabic manuscripts, many of which were smuggled out of Timbuktu beginning in 2012, after Islamic militants who had seized control of the city began damaging or destroying many objects of great historical and cultural value.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!