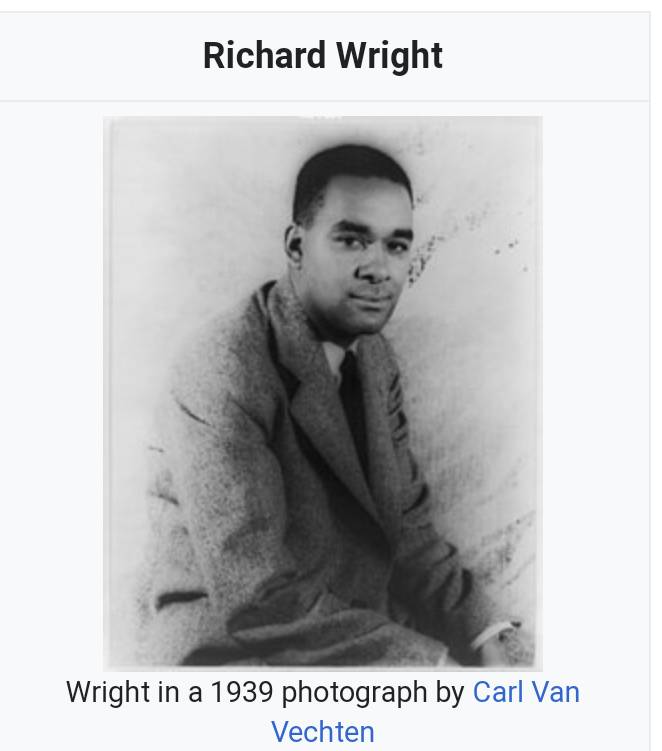

Richard Nathaniel Wright (September 4, 1908 - November 28, 1960) was an American author of novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction. Much of his literature concerns racial themes, especially related to the plight of African Americans during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries suffering discrimination and violence. Literary critics believe his work helped change race relations in the United States in the mid-20th century.[1]

Early life and education

Childhood in the South

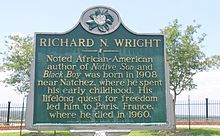

Richard Wright's memoir, Black Boy, covers the interval in his life from 1912 until May 1936.[2] Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908 at Rucker's Plantation, between the train town of Roxie and the larger river city of Natchez, Mississippi.[3] He was the son of Nathan Wright (c. 1880–c. 1940) who was a sharecropper[3] and Ella (Wilson) (b. 1884 Mississippi[4] – d. January 13, 1959 Chicago, Illinois) who was a schoolteacher.[3][5] His parents were born free after the Civil War; both sets of his grandparents had been born into slavery and freed as a result of the war. Each of his grandfathers had taken part in the U.S. Civil War and gained freedom through service: his paternal grandfather Nathan Wright (1842–1904) had served in the 28th United States Colored Troops; his maternal grandfather Richard Wilson (1847–1921) escaped from slavery in the South to serve in the US Navy as a Landsman in April 1865.[6]

Richard's father left the family when Richard was six years old, and he did not see Richard for 25 years. In 1911 or 1912 Ella moved to Natchez, Mississippi to be with her parents. While living in his grandparents' home, he accidentally set the house on fire. Wright's mother was so mad that she beat him until he was unconscious.[7][8] In 1915 Ella put her sons in Settlement House, a Methodist orphanage, for a short time.[7][9] He was enrolled at Howe Institute in Memphis from 1915 to 1916.[3] In 1916 his mother moved with Richard and his younger brother to live with her sister Maggie (Wilson) and Maggie's husband Silas Hoskins (born 1882) in Elaine, Arkansas. This part of Arkansas was in the Mississippi Delta where former cotton plantations had been. The Wrights were forced to flee after Silas Hoskins "disappeared," reportedly killed by a white man who coveted his successful saloon business.[10] After his mother became incapacitated by a stroke, Richard was separated from his younger brother and lived briefly with his uncle Clark Wilson and aunt Jodie in Greenwood, Mississippi.[3] At the age of 12, he had not yet had a single complete year of schooling. Soon Richard with his younger brother and mother returned to the home of his maternal grandmother, which was now in the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi, where he lived from early 1920 until late 1925. His grandparents, still mad at him for destroying their house, repeatedly beat Wright and his brother.[8] But while he lived there, he was finally able to attend school regularly. He attended the local Seventh-day Adventist school from 1920 to 1921, with his aunt Addie as his teacher.[3][7] After a year, at the age of 13 he entered the Jim Hill public school in 1921, where he was promoted to sixth grade after only two weeks.[11] In his grandparents' Seventh-day Adventist home, Richard was miserable, largely because his controlling aunt and grandmother tried to force him to pray so he might build a relationship with God. Wright later threatened to move out of his grandmother's home when she would not allow him to work on the Adventist Sabbath, Saturday. His aunt's and grandparents' overbearing attempts to control him caused him to carry over hostility towards biblical and Christian teachings to solve life's problems. This theme would weave through his writings throughout his life.[9]

At the age of 15, while in eighth grade, Wright published his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre," in the local Black newspaper Southern Register. No copies survive.[9] In Chapter 7 of Black Boy, he described the story as about a villain who sought a widow's home.[12]

In 1923, after excelling in grade school and junior high, Wright earned the position of class valedictorian of Smith Robertson Junior High School from which he graduated in May 1925.[3] He was assigned to write a speech to be delivered at graduation in a public auditorium. Before graduation day, he was called to the principal's office, where the principal gave him a prepared speech to present in place of his own. Richard challenged the principal, saying "the people are coming to hear the students, and I won't make a speech that you've written."[13] The principal threatened him, suggesting that Richard might not be allowed to graduate if he persisted, despite his having passed all the examinations. He also tried to entice Richard with an opportunity to become a teacher. Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom, Richard refused to deliver the principal's address, written to avoid offending the white school district officials. He was able to convince everyone to allow him to read the words he had written himself.[9]

In September that year, Wright registered for mathematics, English, and history courses at the new Lanier High School, constructed for black students in Jackson—the state's schools were segregated under its Jim Crow laws—but he had to stop attending classes after a few weeks of irregular attendance because he needed to earn money to support his family.[9][2]

In November 1925 at the age of 17, Wright moved on his own to Memphis, Tennessee. There he fed his appetite for reading. His hunger for books was so great that Wright devised a successful ploy to borrow books from the segregated white library. Using a library card lent by a white coworker, which he presented with forged notes that claimed he was picking up books for the white man, Wright was able to obtain and read books forbidden to black people in the Jim Crow South. This strategem also allowed him access to publications such as Harper's, Atlantic Monthly, and American Mercury.[9]

He planned to have his mother come and live with him once he could support her, and in 1926, his mother and younger brother did rejoin him. Shortly thereafter, Richard resolved to leave the Jim Crow South and go to Chicago.[14] His family joined the Great Migration, when tens of thousands of blacks left the South to seek opportunities in the more economically prosperous northern and mid-western industrial cities.

Wright's childhood in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas shaped his lasting impressions of American racism.[15]

Coming of age in Chicago

Wright and his family moved to Chicago in 1927, where he secured employment as a United States postal clerk.[10] He used his time in between shifts to study other writers including H.L. Mencken, whose vision of the American South as a version of Hell made an impression. When he lost his job there during the Great Depression, Wright was forced to go on relief in 1931.[9] In 1932, he began attending meetings of the John Reed Club, a Marxist Party literary organization.[9][16] Wright established relationships and networked with party members. Wright formally joined the Communist Party and the John Reed Club in late 1933 at the urging of his friend Abraham Aaron.[citation needed] As a revolutionary poet, he wrote proletarian poems ("We of the Red Leaves of Red Books", for example), for New Masses and other communist-leaning periodicals.[9] A power struggle within the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club had led to the dissolution of the club's leadership; Wright was told he had the support of the club's party members if he was willing to join the party.[17]

In 1933 Wright founded the South Side Writers Group, whose members included Arna Bontemps and Margaret Walker.[18][19] Through the group and his membership in the John Reed Club, Wright founded and edited Left Front, a literary magazine. Wright began publishing his poetry ("A Red Love Note" and "Rest for the Weary" for example) there in 1934.[20] There is dispute about the demise in 1935 of Left Front Magazine as Wright blamed the Communist Party despite his protests.[21] It is however likely due to the proposal at the 1934 Midwest Writers Congress that the John Reed Club be replaced by a Communist Party-sanctioned First American Party Congress.[citation needed] Throughout this period, Wright continued to contribute to New Masses magazine, revealing the path his writings would ultimately take.[22]

By 1935, Wright had completed the manuscript of his first novel, Cesspool, which was rejected by eight publishers and published posthumously as Lawd Today (1963).[10][23] This first work featured autobiographical anecdotes about working at a post office in Chicago during the great depression.[24]

In January 1936 his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication in the anthology New Caravan and the anthology Uncle Tom's Children, focusing on black life in the rural American South.[25]

In February of that year, he began working with the National Negro Congress, speaking at the Chicago convention on "The Role of the Negro Artist and Writer in the Changing Social Order".[26] His ultimate goal (looking at other labor unions as inspiration) was the development of NNC-sponsored publications, exhibits, and conferences alongside the Federal Writers' Project to get work for black artists.[26]

In 1937, he became the Harlem editor of The Daily Worker. This assignment compiled quotes from interviews preceded by an introductory paragraph, thus allowing him time for other pursuits like the publication of Uncle Tom's Children a year later.[20]

Pleased by his positive relations with white Communists in Chicago, Wright was later humiliated in New York City by some white party members who rescinded an offer to find housing for him when they learned his race.[27] Some black Communists denounced Wright as a "bourgeois intellectual." Wright was essentially autodidactic. He had been forced to end his public education to support his mother and brother after completing junior high school.[28]

Throughout the Soviet pact with Nazi Germany in 1940, Wright continued to focus his attention on racism in the United States.[29] He would ultimately break from the Communist Party when they broke from a tradition against segregation and racism and joined Stalinists supporting the US entering World War II in 1941.[29]

Wright insisted that young communist writers be given space to cultivate their talents. Wright later described this episode through his fictional character Buddy Nealson, an African-American communist in his essay "I tried to be a Communist," published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1944. This text was an excerpt of his autobiography scheduled to be published as American Hunger but was removed from the actual publication of Black Boy upon request by the Book of the Month Club.[30] Indeed, his relations with the party turned violent; Wright was threatened at knife point by fellow-traveler co-workers, denounced as a Trotskyite in the street by strikers, and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 May Day march.[31]