In June of 2004, Arno Rafael Minkkinen stepped up to the microphone at the New England School of Photography to deliver the commencement speech.

As he looked out at the graduating students, Minkkinen shared a simple theory that, in his estimation, made all the difference between success and failure. He called it The Helsinki Bus Station Theory.

The Helsinki Bus Station Theory

Minkkinen was born in Helsinki, Finland. In the center of the city there was a large bus station and he began his speech by describing it to the students.

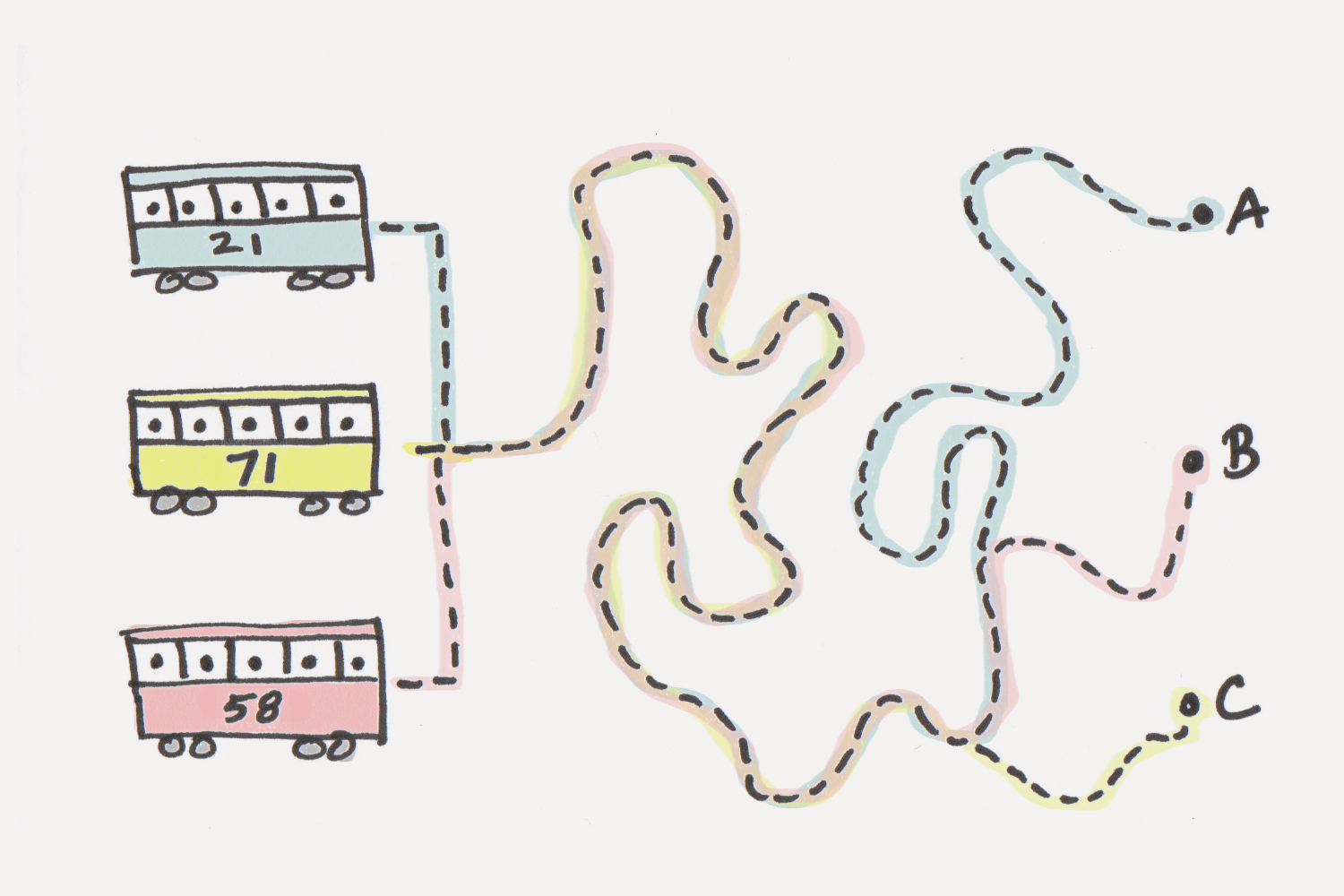

“Some two-dozen platforms are laid out in a square at the heart of the city,” Minkkinen said. “At the head of each platform is a sign posting the numbers of the buses that leave from that particular platform. The bus numbers might read as follows: 21, 71, 58, 33, and 19. Each bus takes the same route out of the city for at least a kilometer, stopping at bus stop intervals along the way.”

He continued, “Now let’s say, again metaphorically speaking, that each bus stop represents one year in the life of a photographer. Meaning the third bus stop would represent three years of photographic activity. Ok, so you have been working for three years making platinum studies of nudes. Call it bus #21.”

“You take those three years of work to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the curator asks if you are familiar with the nudes of Irving Penn. His bus, 71, was on the same line. Or you take them to a gallery in Paris and are reminded to check out Bill Brandt, bus 58, and so on. Shocked, you realize that what you have been doing for three years others have already done.”

“So you hop off the bus, grab a cab—because life is short—and head straight back to the bus station looking for another platform.”

“This time,” he said, “you are going to make 8×10 view camera color snapshots of people lying on the beach from a cherry picker crane. You spend three years at it and three grand and produce a series of works that elicit the same comment. Haven’t you seen the work of Richard Misrach? Or, if they are steamy black and white 8x10s of palm trees swaying off a beachfront, haven’t you seen the work of Sally Mann?”

“So once again, you get off the bus, grab the cab, race back and find a new platform. This goes on all your creative life, always showing new work, always being compared to others.”

“Stay on the Bus”

Minkkinen paused. He looked out at the students and asked, “What to do?”

“It’s simple,” he said. “Stay on the bus. Stay on the f*cking bus. Because if you do, in time, you will begin to see a difference.”

“The buses that move out of Helsinki stay on the same line, but only for a while—maybe a kilometer or two. Then they begin to separate, each number heading off to its own unique destination. Bus 33 suddenly goes north. Bus 19 southwest. For a time maybe 21 and 71 dovetail one another, but soon they split off as well. Irving Penn is headed elsewhere.”

“It’s the separation that makes all the difference,” Minkkinen said. “And once you start to see that difference in your work from the work you so admire—that’s why you chose that platform after all—it’s time to look for your breakthrough. Suddenly your work starts to get noticed. Now you are working more on your own, making more of the difference between your work and what influenced it. Your vision takes off. And as the years mount up and your work begins to pile up, it won’t be long before the critics become very intrigued, not just by what separates your work from a Sally Mann or a Ralph Gibson, but by what you did when you first got started!”

“You regain the whole bus route in fact. The vintage prints made twenty years ago are suddenly re-evaluated and, for what it is worth, start selling at a premium. At the end of the line—where the bus comes to rest and the driver can get out for a smoke or, better yet, a cup of coffee—that’s when the work is done. It could be the end of your career as an artist or the end of your life for that matter, but your total output is now all there before you, the early (so-called) imitations, the breakthroughs, the peaks and valleys, the closing masterpieces, all with the stamp of your unique vision.”

“Why? Because you stayed on the bus.”

Does Consistency Lead to Success?

I write frequently about how mastery requires consistency. That includes ideas like putting in your reps, improving your average speed, and falling in love with boredom. These ideas are critical, but The Helsinki Bus Station Theory helps to clarify and distinguish some important details that often get overlooked.

Does consistency lead to success?

- Consider a college student. They have likely spent more than 10,000 hours in a classroom by this point in their life. Are they an expert at learning every piece of information thrown at them? Not at all. Most of what we hear in class is forgotten shortly thereafter.

- Consider someone who works on a computer each day at work. If you've been in your job for years, it is very likely that you have spent more than 10,000 hours writing and responding to emails. Given all of this writing, do you have the skills to write the next great novel? Probably not.

- Consider the average person who goes to the gym each week. Many folks have been doing this for years or even decades. Are they built like elite athletes? Do they possess elite level strength? Unlikely.

The key feature of The Helsinki Bus Station Theory is that it urges you to not simply do more work, but to do more re-work.

It's Not the Work, It's the Re-Work

Average college students learn ideas once. The best college students re-learn ideas over and over. Average employees write emails once. Elite novelists re-write chapters again and again. Average fitness enthusiasts mindlessly follow the same workout routine each week. The best athletes actively critique each repetition and constantly improve their technique. It is the revision that matters most.

To continue the bus metaphor, the photographers who get off the bus after a few stops and then hop on a new bus line are still doing work the whole time. They are putting in their 10,000 hours. What they are not doing, however, is re-work. They are so busy jumping from line to line in the hopes of finding a route nobody has ridden before that they don't invest the time to re-work their old ideas. And this, as The Helsinki Bus Station Theory makes clear, is the key to producing something unique and wonderful.

By staying on the bus, you give yourself time to re-work and revise until you produce something unique, inspiring, and great. It’s only by staying on board that mastery reveals itself. Show up enough times to get the average ideas out of the way and every now and then genius will reveal itself.

Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers popularized The 10,000 Hour Rule, which states that it takes 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to become an expert in a particular field. I think what we often miss is that deliberate practice is revision. If you're not paying close enough attention to revise, then you're not being deliberate.

A lot of people put in 10,000 hours. Very few people put in 10,000 hours of revision. The only way to do that is to stay on the bus.

Which Bus Will You Ride?

We are all creators in some capacity. The manager who fights for a new initiative. The accountant who creates a faster process for managing tax returns. The nurse who thinks up a better way of managing her patients. And, of course, the writer, the designer, the painter, and the musician laboring to share their work out to the world. They are all creators.

Any creator who tries to move society forward will experience failure. Too often, we respond to these failures by calling a cab and getting on another bus line. Maybe the ride will be smoother over there.

Instead, we should stay on the bus and commit to the hard work of revisiting, rethinking, and revising our ideas.

In order to do that, however, you must answer the toughest decision of all. Which bus will you ride? What story do you want to tell with your life? What craft do you want to spend your years revising and improving?

How do you know the right answer? You don’t. Nobody knows the best bus, but if you want to fulfill your potential you must choose one. This is one of the central tensions of life. It’s your choice, but you must choose.

And once you do, stay on the bus.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!