On the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Immigration Act, I began to embrace my Asian identity

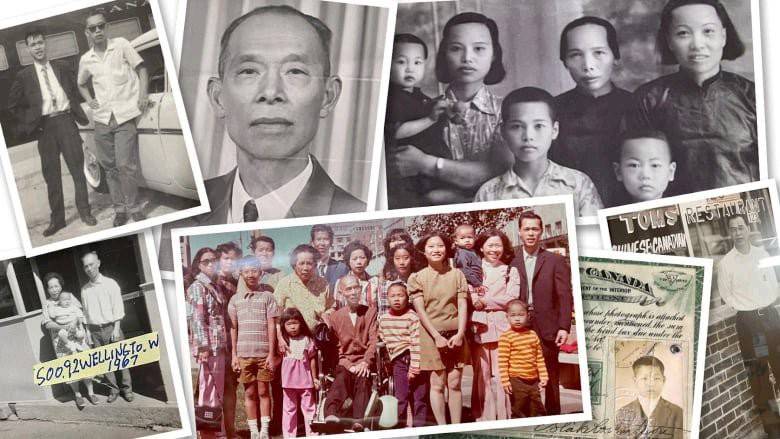

(Courtesy Winston Ma)

「前人種樹,後人乘涼」"The predecessors plant trees and the descendants enjoy the shade." – Chinese proverb

Translation: Read this story in Traditional Chinese

For the first 37 years of my life, I'd lived confidently believing that my family, like many Chinese Canadians, had begun our lives in Canada as part of a wave of immigration from Hong Kong and beyond during the 1970s. And then last year, in the middle of the pandemic and amid a surge of anti-Asian sentiment, I started to dig deeper into my family's past and discovered that it wasn't our first time as settlers in Canada. Our story began more than 100 years ago, in the era of the Chinese Head Tax and The Chinese Exclusion Act, when the government was determined to prevent people who looked like me from becoming citizens of this country.

Photo of my great grandparents beside two of their children taken in Taishan, China in the 1930s. The child on the far right would become my maternal grandmother. It would take more than 30 years for her to be reunited with her father in Canada. (Courtesy Winston Ma)

As a young jook-sing — a Cantonese slang phrase for a Western-born and/or raised Chinese person who identifies more with Western than Chinese culture — in north Scarborough, I was more concerned about erasing all traces of my Chinese identity than learning about where my family came from. And you can imagine why. You see, I never saw myself in North American media, TV or film. There were never any stories that were by and about people like me. The only portrayals of Asians at the time were pumped full of stereotypical tropes: yellow- facing in shows such as Kung Fu starring David Carradine, we were background extras that were weak and sex-less, and/or we were the evil, conniving "Fu Manchu" character. I became so ashamed of being Chinese that it was easier for me to come to terms with my queer identity at 13 years old than my ethnic background.

Back in school, little was taught about Chinese Canadians ( let alone stories from Indigenous peoples and other non-European communities) in history class. If we were mentioned, it was one tiny, you-had-to-find-it- using-a-magnifying-glass, paragraph about the Chinese Head Tax or Chinese working on the railway. From the education system to pop culture, zero value was placed on the stories of Chinese Canadians; it's no wonder my impressionable young mind thought this meant that my family and I didn't matter, and didn't belong here.

But my world changed last year: I became a born- again Asian. Like so many of my fellow Asian Canadians, I was grappling with the anti-Asian racism that reared its ugly head during the pandemic. In doing so, I began to reclaim the Chinese heritage that I had shunned my whole life.

(l) - My great grandparents Lee Chuen Oy and May Lee, holding their grandson David Lee in front of their Sault Ste Marie restaurant "Oy's Restaurant/Lunch" in 1967| (r) Photo of my uncle Donald Lee in front of Tom's Restaurant, Toronto, that he operated with his wife since the 1960s (Courtesy Winston Ma)

When my maternal grandfather passed away last summer, I learned that he had owned a Chinese restaurant at Bay and Dundas Streets in Toronto during the 1980s. Hungry to learn more, I devoured the best- selling books Chop Suey Nation by Ann Hui and Have You Eaten Yet? by Cheuk Kwan. Both books use the ubiquitous Chinese restaurant — like my grandfather's — found across Canada and beyond, to chart a living atlas of the Chinese diaspora in Canada (Chop Suey Nation) and elsewhere in the world (Have You Eaten Yet?).

WATCH: House Special chronicles the Chinese Canadian experience through the lens of small- town Asian restaurants and the families that run them.

When I raved about these books during my family's Christmas dinner, my mom, pleasantly surprised that I'd taken an interest in our people's stories, added one of her own: "You know your great-grandfather paid the Chinese Head Tax when he came to Canada, right?" My siblings and I almost choked on our food when we heard this. "Waaiiit! What do you mean?" With another no- big-deal-sounding answer, my mom declared, "I thought I told you before? He came here in the early 1900s, paid the Head Tax and eventually settled in Sault Ste. Marie to run our family's restaurant."

(Courtesy Winston Ma)

The following week was a game of catch-up with me desperately trying to glean as much information about my ancestor as possible from my mom and my aunt Fanny, her younger sister. I had so many questions, but so few answers.

After a week and a half of going down the digital rabbit hole, I stumbled upon the invaluable research by Professors Peter Ward and Henry Yu of the Department of History at UBC. They digitized records of all recorded individuals listed in the Register of Chinese Immigrants to Canada who paid the Chinese Head Tax from 1886-1949 and compiled them in one Excel sheet. I sifted through 97,123 listed names using whatever scant detail I had about my great-grandfather. And then on line 85,772, a name popped up that sounded familiar. After triple-checking the details — his home village, his height, his listed occupation and his intended final destination — I found him

My great grandfather's C.I. 5 Chinese Head Tax certificate, indicating he had paid $500 in 1918 just to enter the country. These certificates were issued by the Canadian Government only to Chinese immigrants. (Courtesy Winston Ma)

Through these records and conversations with my family — including my Uncle Donald, his only surviving child — I'd like to introduce you to my great-grandfather, Lee Chuen Oy ( as it was transcribed by the immigration official). He came to Canada, to "Gold Mountain" (in Cantonese, a commonly-used nickname referring to North America) to escape poverty, war and famine in the Taishan region of southern China. On January 23, 1918, he disembarked from the SS Empress of Japan in Victoria, B.C. He was recorded in the General Register of Chinese Immigration of 1918 as being 15 years old, a student and four feet, five inches in height.

(r) - A portrait photo of Lee Wan Sze, my great- great-grandfather who was the first in his family to arrive in Canada at some point around the turn of the century | (l) My great-grandfather Lee Chuen Oy as an adult. (Courtesy Winston Ma)

On arrival, he was forced to pay the $500 Chinese Head Tax to enter the country. He then travelled all the way to London, Ontario to meet his father, Lee Wan Sze. Yes, I was surprised to discover that my great- great-grandfather was, in fact, the first in our family to arrive in Canada ( at some point around the turn of the century) but he went back to China a few years after his son arrived, and never returned.

Lee Chuen Oy, meanwhile, started a laundry business in southern Ontario, but an opportunity to run his own restaurant in Sault Ste. Marie led him north. For the next few decades, he toiled away at Oy's Restaurant/Lunch, located at 92 Wellington Street West. He was eager to bring his family to this land and begin a life together, but those dreams were stolen from him in 1923 with the introduction of The Chinese Immigration Act ( commonly called the Chinese Exclusion Act), which banned the entry of virtually all Chinese immigrants. It was the first and only immigration law that banned entry by race, and it would keep people like my great-grandfather, other naturalized Chinese immigrants and born-and-raised-in-Canada Chinese from bringing over their families until the law was repealed in 1947. In order to marry and start a family, he would have been able to take limited trips back to China, and return to Canada within two years or lose his status.

During this time, white people, specifically from Commonwealth nations, were given huge financial incentives to become settlers in Canada. With The Empire Settlement Act of 1922, the Canadian government entered into an agreement with the British government to subsidize their citizens to work in Canada and to ensure "British values" dominated. These British immigrants were even encouraged to bring over friends and acquaintances, while people like my great-grandfather, who had paid dearly to enter Canada, were forced to become "married bachelors," unable to bring over even their most immediate family members.

Photo taken in 1954 of my uncle Donald Lee (the suited child in the middle holding a duffle bag) at Kai Tak airport in Hong Kong before his journey to Canada to meet his father, Lee Chuen Oy, for the first time. (Courtesy Winston Ma)

In the early 1950s, my great-grandfather was finally allowed to bring over some of his family. His wife, May Lee, and two of his children were the first to arrive in Canada, which included my Uncle Donald who was just a pre- teen at the time. The rest of his family, which included my mom and relatives, weren't allowed in until the 1970s. They only had about a year or two to finally live together as one big family before my great-grandfather and his wife passed away in 1973 and 1974 respectively.

My entire family was finally reunited in the early 1970s — over five decades after Lee Chuen Oy arrived in Canada — when immigration restrictions based on race and national origin were finally fully scrubbed in 1967. This was one of the last photos of my great grandfather took before he died in 1973. (Courtesy Winston Ma)

For many Asian Canadians, the pandemic forced us to confront some uncomfortable truths. From being blamed for giving the world "Kung flu", asked, "Where are you from? No, where are you really from?" our entire lives, to seeing our elders violently attacked and others killed, it's become clear that no matter how integrated we are in Canadian society, we are first viewed as Asian — foreign, never quite fully belonging or loyal to this country. I've had to acknowledge this othering and finally start to unpack the racism I'd internalized since childhood.

With this year marking 100 years since the Chinese Immigration Act was passed, I have begun to take pride in my background. Having pieced together my own family's journey to Canada, I am able to paint a better picture of where I descended from so I can honour my ancestors and their sacrifices.

My ancestors — like my great-grandfather Lee Chuen Oy — were brave and strong. They faced an unwelcoming environment and they persevered. They were resilient in the face of adversity, never once complaining about the racist society and government that stole their dreams when they were trying to build lives, businesses and families.

(Courtesy Winston Ma ( second from right))

Hundreds of thousands of Chinese Canadians moved mountains so the next generations could climb to the summit of "Gold Mountain." I now know where my strength and determination come from. It took me 37 years but I can now finally say that I have never been more proud to be Chinese Canadian

This Asian Heritage Month, we asked Asian Canadian content creators to tell us what #IAmAsianEnough means to them. Check out @CBC Instagram posts all May hear more stories.

WATCH: Celebrate Asian Heritage Month with a collection of documentaries, films and shows that honour the rich culture and talent of Asian Canadians.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!