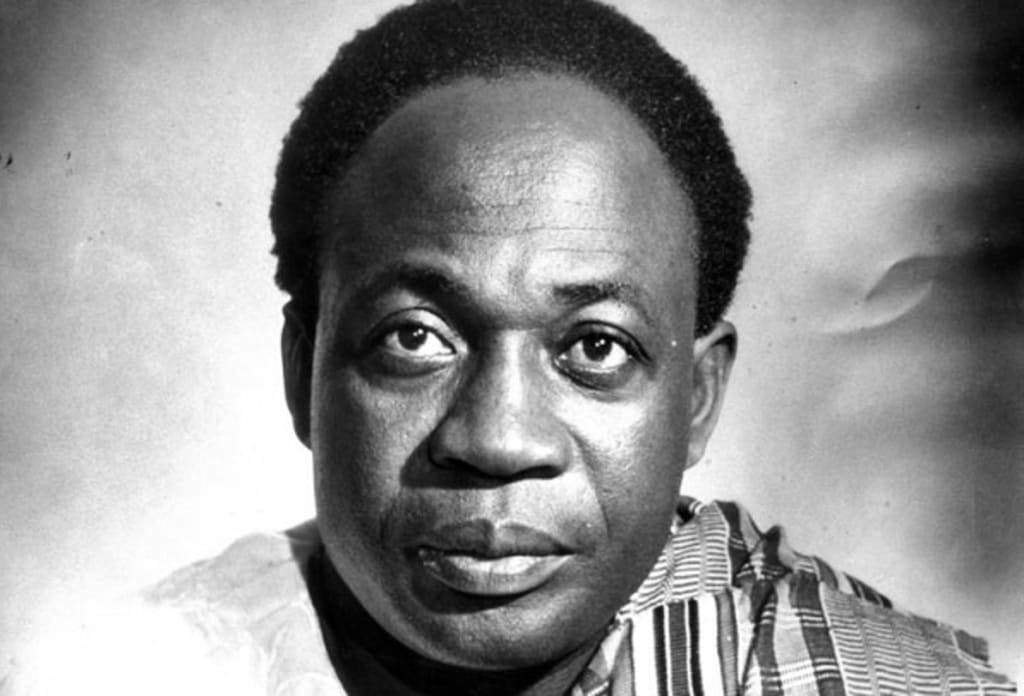

The name Kwame Nkrumah is synonymous with Ghanaian independence and pan-Africanism. Often referred to as "Africa's Gandhi", Nkrumah was instrumental in leading Ghana to become the first sub-Saharan African country to break free from colonial rule.

Nkrumah’s journey began in the small Nzima village of Nkroful in the Western Region of the British colony known as the Gold Coast. Born Francis Nwia Kofi Ngonloma in 1909, Nkrumah was raised by his goldsmith father Kofi Ngonloma and trading mother Elizabeth Nyanibah. He excelled in his studies at the prestigious Achimota College and became a school teacher at the age of 20. Dissatisfied with the racist treatment of Africans under colonial rule, Nkrumah left for America in 1935 to continue his education at the historically black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

It was during his time in America that Nkrumah was exposed to the philosophies of Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. Du Bois and other pan-Africanist thinkers. He immersed himself in books about socialism, organizing tactics, and African history. By the time he moved to London in 1945, Nkrumah was committed to the ideal of pan-Africanism - the unification and liberation of all people of African descent.

In London, Nkrumah helped organize the landmark 5th Pan-African Congress which strengthened ties between black intellectuals and activists around the world. When he returned home to the Gold Coast in 1947, Nkrumah had a new name and a fire in his belly to challenge British colonial rule.

Alongside other nationalist leaders like Joseph Boakye Danquah and Emmanuel Obetsebi-Lamptey, Nkrumah formed the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) and was named Secretary-General. As the UGCC's spokesman, he traveled around the colony gathering support and advocating for independence. But the UGCC's tactics were too gradualist for the zealous Nkrumah, and he set out on his own to form the more radical Convention People’s Party (CPP) in 1949.

Nkrumah’s calls for immediate self-government landed him in prison from 1950-1951. But imprisonment only increased his prestige among ordinary people, and the CPP swept to victory in the 1951 elections. Released from prison to become Leader of Government Business, Nkrumah led subsequent negotiations with the British that culminated in Ghanaian independence on March 6, 1957.

The day that the beloved black, green, and gold flag was unfurled for the first time was one of joyous celebration in Accra and around the country. Finally, after decades of colonial rule, Ghana was free to chart its own course. The momentous occasion was hailed across Africa and the diaspora as a milestone in the continent's liberation struggle.

As the first Prime Minister and then President of independent Ghana, Nkrumah sought nothing less than the total liberation and unification of Africa. He made Accra the headquarters of the pan-African movement, hosting activists and supporting liberation struggles across the continent. Nkrumah was instrumental in the founding of the Organization of African Unity, the precursor to today’s African Union.

Domestically, Nkrumah's government invested heavily in industrialization and development projects, driven by the president's socialist leanings. Major infrastructure projects like the Akosombo Dam, Tema Harbor, and highways crisscrossing the country bolstered the economy in the early years. Healthcare, education, and women's rights also improved under Nkrumah's social welfare policies.

However, Nkrumah met resistance to his authoritarian governing style and intolerance of political opposition. When he declared Ghana a one-party state in 1964 after a narrowly won referendum, critics decried him as a dictator. Multiple assassination attempts followed, along with bombings linked to his political opponents.

The struggling economy also weakened Nkrumah's popularity over time. Over-ambitious industrial projects floundered, food shortages occurred, and the country became increasingly dependent on cocoa exports. By 1966, his detractors had had enough, and while Nkrumah was on a peace mission to China, the military overthrew his government in a coup.

Nkrumah lived the rest of his years in exile in Guinea, home to another key pan-Africanist, President Sekou Toure. He continued writing and advocating for African unity until his death from cancer in 1972. Though his socialist policies and authoritarian tendencies remain controversial, Nkrumah is honored as a founding father of independent Ghana and a dedicated pan-Africanist.

His vision for African unity has yet to come to full fruition, but the African Union continues to be guided by Nkrumah's words: "Divided we are weak; united, Africa could become one of the greatest forces for good in the world.†Ghana celebrates his birthday each September 21st as a Founder’s Day holiday, in remembrance of the man Ghanaians call "Osagyefo"- the redeemer.